|

The Domestic Workers Convention 2011: Implications for migrant domestic workers in Southeast Asia

The recent International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Convention 2011) offers an opportunity to finally address the longstanding issue of the protection of the human and labour rights of migrant domestic workers. This NTS Insight evaluates the responses of four Southeast Asian states – Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia and Singapore – to the Convention. It highlights continuing differences between labour sending and labour receiving countries in terms of their responses, and suggests that ASEAN could play a significant role in bridging that gap and promoting the adoption of universal standards and practices.

By Pau Khan Khup Hangzo and Alistair D.B. Cook

| A group of domestic workers rejoicing after the result of the vote on the Domestic Workers Convention at the 100th Conference of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in Geneva on 16 June 2011.

Credit: ILO. |

|

Contents:

Recommended citation: Hangzo, Pau Khan Khup and Alistair D.B. Cook, 2012, ‘The Domestic Workers Convention 2011: Implications for migrant domestic workers in Southeast Asia’, NTS Insight, April, Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies.

| |

Introduction

Migrant domestic workers remain one of the least protected groups of workers. The lack or absence of protection means that they are highly vulnerable to a wide range of abuses and exploitation which in its worst forms amount to forced labour and slavery. The abuse and exploitation of migrant domestic workers could potentially increase tensions between labour sending and receiving countries and lead to regional instability. For example, cases of abuse and exploitation of Indonesian domestic workers in Malaysia in 2010 led protesters in Indonesia to stir up nationalistic sentiments, using slogans such as ‘Crush Malaysia’ and demanding that Malaysians leave Indonesia (Indonesians vent, 2010). Thus, a careful management of the migrant domestic-work sector is necessary not only to protect the (human and labour) rights of migrant domestic workers but also to maintain regional peace and security.

This NTS Insight observes that the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Convention concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Convention 2011, also referred to as Convention No. 189), which was adopted on 16 June 2011, offers a historic opportunity to address the longstanding discrimination against migrant domestic workers, who often do not have the same protection under states’ laws as other categories of workers. This NTS Insight specifically explores the responses of Indonesia and the Philippines as labour sending countries, and Malaysia and Singapore as labour receiving countries. Based on the analysis, it discusses how these two sets of countries could standardise their labour laws in order to accommodate the protection needs of migrant domestic workers. It also explores the role of ASEAN in promoting and driving progress on this front.

^ To the top

Migrant domestic workers: A vulnerable labour sector Migrant domestic workers routinely encounter exploitative working conditions, the most prominent of which include excessively long working hours, lack of rest days or rest periods, poor living accommodation, restrictions on freedom of movement and association, and non-payment of salaries. One of the reasons for the exploitation is that work performed by migrant domestic workers is associated with unpaid work performed by mothers and housewives and is often not considered a real job. The migrant domestic-work sector is therefore undervalued. Also, domestic workers live and work in their employer’s house, an arena that is not legally recognised as a workplace. As such, protection rules and the mechanisms of state regulation such as labour inspections do not apply. Indeed, ideologies of ‘domesticity’ and ‘privacy’ have historically combined to provide a justification for exempting domestic workers from some of the basic legal entitlements available to other workers (Ramirez-Machado, 2003).

Tasks performed by domestic workers remain undefined. They may include cooking, cleaning, taking care of children, the elderly, the disabled or even domestic animals.

Credit: Sherwin Huang / flickr.

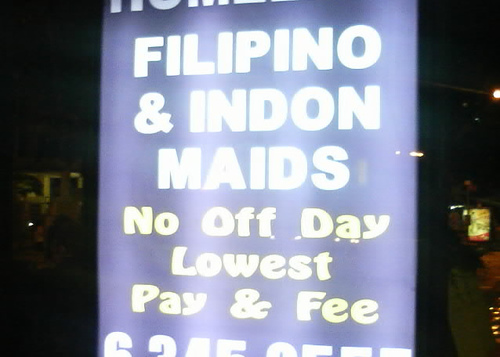

Also, unfair portrayal by the media has resulted in the tacit legitimisation of the strict control of migrant domestic workers by employers (and the state). Migrant Rights, a website dedicated to raising awareness on the plight of migrant workers in the Middle East, observed that there is a disproportional fixation on migrant domestic-worker crimes in the Middle East. Media across the region are found to report on domestic-worker crimes without adequate context when in effect crimes committed by domestic workers are, in most cases, the product of abuse (Employer’s cruelty, 2012). Employer abuse, on the other hand, only makes the headlines sporadically. Domestic workers are also regularly cast by the media as ‘devious’, ‘untrustworthy’, ‘savagely unpredictable’, ‘abusive sneaky witches’, ‘lazy liars’, ‘thief’ and ‘criminals’ (Gulf’s domestic workers, 2011; Migrant domestic workers, 2010). Dato’ Hj. Abdul Hamid (2009) observes that advertisements in Malaysia construct domestic workers as non-individuals and non-human. They are seen as objects/commodities that are expendable and subservient. In Singapore, a blog for the sharing of employers’ negative domestic-worker experiences was criticised for reinforcing many of the social biases and prejudices held by Singaporeans (Lin, 2011).

The cumulative effect of such stereotyping of migrant domestic workers is to further damage the already negative image of migrant domestic workers in labour receiving countries, leading to an endorsement of what Migrant Rights calls ‘domestic dictatorships’ (Gulf’s domestic workers, 2011). In Singapore, employers are reluctant to give a weekly day off to domestic workers due to the perceived ‘social problems’ associated with a day off such as the belief that domestic workers might ‘find boyfriends’ and ‘fall pregnant’ (Chok, 2011).

^ To the top

Enhancing protection standards: Domestic Workers Convention 2011

The lack of government regulations means that domestic workers often remain at the mercy of employment agencies and employers.

Credit: mr brown / flickr. At the 100th annual Conference of the International Labour Organization (ILO) held on 16 June 2011, ILO representatives, who are from governments, trade unions and employers’ organisations, adopted the Domestic Workers Convention and the accompanying Recommendation concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Recommendation 2011, also referred to as Recommendation No. 201) (ILO, 2011a). The Convention, which is legally binding, lays down basic principles and measures for the promotion of decent work for domestic workers. The Recommendation, on the other hand, is a non-binding instrument that offers practical guidance for the strengthening of national laws and policies on domestic work.

The provisions in the Convention are especially relevant to the needs and risks faced by migrant domestic workers. Member states are required by the Convention to cooperate with each other to ensure the effective application of the provisions of the Convention to migrant domestic workers. States must also make it mandatory for migrant domestic workers to receive a written contract that is enforceable in the country of employment – or a written job offer – prior to travelling to the country of employment. The contract or job offer should list the terms and conditions of employment. Member states must also implement measures aimed at ensuring that the conditions under which domestic workers are entitled to repatriation at the end of their employment are specified. The key provisions and measures in the Convention and its accompanying Recommendation are summarised in Box 1.

The Convention is a major step forward in ensuring the human and labour rights of migrant domestic workers. However, how well is it received in Southeast Asia which is home to both labour sending as well as labour receiving states? The next section of this NTS Insight looks at the responses of four states in Southeast Asia, both in terms of their responses to migrant domestic-worker issues more generally, and to the Convention more specifically.

|

Box 1: Domestic Workers Convention 2011 and its accompanying Recommendation – Summary.

|

The following is a summary of the provisions and measures in the Convention concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Convention 2011, also referred to as Convention No. 189) and the Recommendation concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Recommendation 2011, also referred to as Recommendation No. 201):

- Fundamental principles and rights at work.

- Freedom of association and the recognition of the right to collective bargaining.

- Elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour.

- Abolition of child labour.

- Elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

- Information on the terms and conditions of employment.

- Workers should receive a written contract. This requirement does not however apply to migrant domestic workers who are already within the territory of the country of employment. It also does not apply either to workers who benefit from freedom of movement for the purpose of employment between the countries concerned, either under bilateral, regional or multilateral agreements, or within the framework of a regional economic integration area.

- Fair terms of employment, including decent working and living conditions.

- Working hours: normal working hours, overtime compensation, annual paid leave, as well as periods of daily and weekly rest.

- Remuneration: minimum wages, non-discrimination and the protection of remuneration.

- Social security including maternity benefits.

- Occupational safety and health.

- Protection from abuse, harassment and violence.

- Protection for particular groups of domestic workers, namely, child domestic workers, live-in domestic workers, and migrant domestic workers.

- Regulation of private employment agencies.

- Compliance and enforcement, through dispute settlement and complaint mechanisms such as court and tribunals, labour inspection, penalties, etc.

|

Source: ILO (2011b).

|

^ To the top

Policy responses of labour sending countries

It should come as no surprise that Indonesia and the Philippines voted in favour of the Domestic Workers Convention. As labour surplus countries, the export of migrant domestic workers is seen by the two countries as an important strategy for addressing unemployment, generating foreign exchange and fostering economic growth (Hangzo et al., 2011). The two countries’ support for the Convention is therefore in line with their ongoing efforts to protect their migrant domestic workers.

Indonesia

President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, in expressing his country’s support for the Domestic Workers Convention, noted that it could provide ‘guidance to the sending and host governments to protect migrant domestic workers’ and that it will help Indonesia ‘formulate effective national legislation and regulations for this purpose’ (ILO, 2011c).

Workers from Indonesia account for about half of the estimated 201,000 migrant domestic workers in Singapore (Tan, 2012) and about 80 per cent of Malaysia’s 350,000 migrant domestic workers (Soeriaatmadja, 2012). These workers are often subjected to abuse and exploitation. In response, Indonesia has stepped up its efforts to protect its workers. The country signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Malaysia in June 2011 (RI-Malaysia MoU, 2011). The MOU specifies that Indonesian migrant domestic workers should be granted a weekly day off and allowed to keep their passports.

To protect would-be migrants during the recruitment process in Indonesia, the country announced new rules for passport applications in early 2012. Previously, would-be migrants would apply for passports in far-flung cities like Jakarta after they are selected by a maid agency in receiving countries. Under the new rules, a would-be migrant would have to first obtain a recommendation to work abroad. She would then have to apply for a passport at an immigration office near her hometown (Tan, 2012). The Indonesian Manpower Ministry claimed that this would enable them to ‘know all data on their residents who go to overseas for work’ and help reduce cases of women who lie about their age or qualifications. Indonesia is also working on a new policy called the ‘live-out system’ under which Indonesian migrant domestic workers will be housed in dormitories instead of living with their employers (Govt trying, 2011). In addition, the country has developed the Domestic Worker Roadmap 2017 under which it plans to stop sending domestic workers abroad after 2017 unless receiving countries recognise them as formal workers and grant them all the necessary rights (Soeriaatmadja, 2012).

The Philippines

The Philippines, as Chairman of the Domestic Workers Convention negotiating process, sees the adoption of the Convention as ‘a major victory for Filipino domestic workers’ (Dioquino, 2011). In order to hasten its ratification, a resolution was filed in the Philippine parliament on 4 October 2011 urging the Benigno Aquino administration to ‘immediately consider the Philippines’ entry as a state party to the International Labour Organization Convention No. 189 … bearing in mind the legal and social benefits that would insure the protection for our local and overseas Filipino domestic workers’ (Philippines, 2011). The Philippines’ interest in ratifying the Convention is further proof of its determination to grant maximum protection to its migrant domestic workers.

The country has already instituted a wide array of laws, the most significant of which is the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act 1995 (also known as Republic Act No. 8042). The Act was introduced for the ‘protection and promotion of the welfare of migrant workers, their families and overseas Filipinos in distress, and for other purposes’ (Philippines, 1995). It includes a number of provisions pertaining to the conditions for deployment; penalties for illegal recruitment; services such as travel advisory, emergency repatriation, legal assistance, etc.; and the detailing of government agencies overseeing the welfare of migrant workers. The most recent amendment to the Act, Republic Act No. 10022, took effect on 13 August 2010.

In 2006, the Philippines introduced a set of policies to strengthen the protection of Filipino domestic workers. Known as the Household Service Workers Reform Package, it specifies the following: the minimum age of Filipino domestic workers should be 23 years old; workers should attend a comprehensive pre-departure education programme; workers should not have to pay placement fees; and a minimum wage of USD400 should be provided (Battistella and Asis, 2011). The provisions of the reform package have since served as a blueprint for bilateral negotiations between the Philippines and labour receiving countries.

It can be observed then that the labour sending countries of Indonesia and the Philippines generally recognise the protection concerns of their migrant domestic workers and have taken steps to address them. However, without complementary actions by labour receiving countries, their efforts have limited impact. The next section will look at the responses of receiving countries to the Domestic Workers Convention and the measures instituted to protect migrant domestic workers in those countries.

^ To the top

Policy responses of labour receiving countries

This section analyses the responses of two major labour receiving countries in Southeast Asia, namely, Malaysia and Singapore, to the Domestic Workers Convention. Unlike labour sending countries, receiving countries have been less willing to support the Convention. Malaysia and Singapore both felt that they could address the concerns of migrant domestic workers within the framework of their existing laws. They did not therefore see the need to be part of a legally binding treaty such as the Convention.

Malaysia

Malaysia, which is home to an estimated 350,000 migrant domestic workers, abstained from voting on the Domestic Workers Convention. It argued that domestic work is not ‘ordinary employment’ and therefore a legally binding treaty would compromise the rights of householders and create unrealistic obligations for employers (ILO, 2011d:6).

The main law that regulates the working conditions of migrant workers, the Employment Act of 1955, excludes migrant domestic workers from key labour rights such as limits to hours of work, a weekly day off, minimum wage, overtime pay, annual leave, etc. Rather than a wholesale amendment of its law to accommodate the standards set by the Convention, Malaysia prefers to address issues of exploitation and abuse of migrant domestic workers on a case-by-case basis – through bilateral agreements with labour sending countries. For example, as highlighted in the previous section, it has agreed to a standard contract guaranteeing Filipino domestic workers a minimum wage of USD400 per month and basic protection of their rights. It has also granted Indonesian domestic workers some rights following an agreement signed in 2011. However, this approach of selective deals with labour sending countries has resulted in discrimination against migrant domestic workers based on their nationalities. For example, Indonesian and Cambodian domestic workers earn significantly lower wages and enjoy far fewer rights than their Filipino counterparts.

Organisations such as the Bar Council of Malaysia have pleaded for state intervention on the issue. In a recommendation submitted to Malaysia’s Ministry of Human Resources in 2009, the Bar Council demanded adequate legal protection for migrant domestic workers and proposed the adoption of a standard employment contract for all such workers irrespective of their country of origin (Kesavan, 2009; see Box 2).

|

Box 2: Standard contract for migrant domestic workers – Recommendations.

|

In their submission to Malaysia’s Ministry of Human Resources, the Bar Council of Malaysia provided a list of items that should be included in a standard contract for migrant domestic workers:

- Place of employment. This is to ensure that the domestic worker is not taken from one place of employment to another.

- Duration of the contract and date of commencement.

- Basic monthly salary.

- Working hours. At least 12 hours a day of rest should be provided, inclusive of a continuous period of rest of at least 7 hours.

- Rest day. Workers should be given one rest day per week. The amount payable if work is done on a rest day should be specified.

- Paid annual leave.A total of 8–12 days per year depending on the duration of work.

- Medical treatment and paid sick leave.

- Bank account bearing domestic worker’s name.

- Wages to be paid directly into the bank account.

- List of all fees and expenses. The fees incurred in the recruitment and employment of the domestic worker should be specified. The amount payable by the employer and the domestic worker should be reflected in the contract.

- Total advances paid by the employer. This should be accompanied by an explanation of how much the employer intends to deduct each month to recover the advances.

- Type of accommodation.

- Meals. Meals should be provided three times a day.

- Size of the household.

- List of duties of domestic worker.

- List of duties or obligations of employer to domestic worker.

- Conditions under which contract is to be terminated.

- Fees and expenses. The cost of bringing in the domestic worker and the cost of repatriation after the natural expiration of contract should be borne by the employer.

- Compensation. The compensation for wrongful termination should be specified.

- Foreign workers compensation scheme. This should include insurance for the domestic worker.

- Passport should remain in the possession of the domestic worker.

- Bank guarantee. A bank guarantee should be provided to the Embassy/High Commission of the sending country.

- Amendments. No provision of the contract can be altered, amended or substituted without the written approval of the Ministry of Human Resources and the Embassy/High Commission of the sending country.

- Copy of contract. One copy of the contract is to be given to the domestic worker in her native language.

|

Source: Kesavan (2009: Appendix 1).

|

^ To the top

Singapore

Like Malaysia, Singapore abstained from voting on the Domestic Workers Convention. Its stated position was that it would sign the treaty only when it was sure that it could implement it. The country did, however, give assurances that it would continue to review the rights and responsibilities of employers and workers.

Migrant domestic workers are a mainstay of Singapore society. It is estimated that 201,000 of them, comprising mostly Indonesians and Filipinos, are currently in the country (Tan, 2012), and that one in five households in Singapore employ a live-in domestic worker (UNIFEM Singapore et al., 2011). However, national labour laws such as the Employment Act of 1968 have not granted them the same rights as other workers.

The need for Singapore to institute measures to protect its migrant domestic workers in line with the Domestic Workers Convention has been highlighted by individuals and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) alike. The Minister of State for Community Development, Youth and Sports, Halimah Yacob, has expressed her support for the Convention and urged Singapore to take its international obligations seriously. Local NGOs such as Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) and the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) have campaigned for domestic workers to be accorded a fair deal at work, decent wages, medical leave, annual paid holidays, regulated work hours, etc. They have also appealed for the ratification of the Domestic Workers Convention and for the inclusion of domestic workers in the Employment Act of 1968 (Heng, 2011).

Singapore has nevertheless avoided wholesale reform and instead pursued piecemeal changes in its migrant domestic-work sector. For example, it announced in June 2011 that mandatory English language testing would be scrapped as it was found to be a major contributor of stress to new arrivals. In its place, a Settling-In Programme with modules on stress management, safety awareness and adapting to life and work abroad would be introduced (MOM, 2011). Commenting on this proposed change, one official from the Ministry of Manpower observed that the mandatory English language testing ‘is not a meaningful measure of quality and does not guarantee that the worker understands the English language’ and instead ‘it discourages some good foreign domestic workers from wanting to work [in Singapore]’ (Hodal, 2011).

Singapore also announced a mandatory weekly rest day for domestic workers in March 2012 (Ng, 2012). This new change will apply to workers whose permits are issued or renewed after January 2013. While these measures are to be lauded, there is a need for a more comprehensive approach that addresses the range of protection issues faced by migrant domestic workers (see Box 3).

|

Box 3: Enhancing the protection of migrant domestic workers in Singapore – Recommendations.

|

The following are key recommendations presented in a report prepared by the Singapore National Committee of the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM Singapore), the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) and Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2):

- Legal protections. Such protections should be granted under the Employment Act or through separate legislation. Full protection, or protection equal to that given to other workers, should be provided.

- Awareness. This could be promoted through rights-based education.

- Education. Areas such as employer-employee relationship management and managing the stresses associated with live-in domestic work should be covered.

- Social support networks for migrant domestic workers. This could help them cope with the stress of live-in domestic work, improve their ability to communicate with employers effectively, and inculcate skills to build a positive and professional relationship with employers.

- Social support networks for employers of migrant domestic workers. This could help them build a positive and professional relationship with their workers, especially in the areas of dispute resolution, and effective communication and management of expectations with regard to job scope and behaviour at work.

- Professionalism of employment agencies. Professional standards in dealing with the hiring of domestic workers needs to be enhanced.

|

Source: UNIFEM Singapore et al. (2011). |

^ To the top

The importance of the Convention for Southeast Asia

As can be seen from the discussion, Indonesia and the Philippines have both introduced significant measures aimed at improving the human and labour rights of their migrant domestic workers, including addressing their working conditions. In practice, however, they have little influence on how their workers are actually treated in labour receiving countries. The recent measures seen in Malaysia and Singapore could help alleviate the plight of migrant domestic workers, but they still do not offer comprehensive protection. Also, they have largely been implemented as a result of bilateral agreements with labour sending countries, and this has in some cases resulted in inequities. For example, such case-by-case agreements have resulted in workers from different countries being offered different wages and conditions.

The Domestic Workers Convention is therefore essential. By establishing universal standards, it offers an opportunity for labour sending and labour receiving countries to institute complementary laws to address migrant domestic-worker concerns. Indonesia and the Philippines have already voted in favour of the Convention. For these two countries, the way forward is to ratify the Convention and to adopt a comprehensive law (or to amend existing labour laws) so as to incorporate the standards enshrined in the Convention. Labour receiving countries such as Malaysia and Singapore have, however, been reticent when it comes to signing the Convention. This NTS Insight suggests that ASEAN could play an important role in encouraging countries in the region to adopt the standards and best practices advocated by the Convention and by local NGOs. The next section discusses this in further detail.

^ To the top

ASEAN: Key forum for regional action

The issue of migrant domestic workers in particular, and migrant workers in general, is a transnational issue as it involves the movement of labour from one country to another. A comprehensive regional approach is therefore vital, not only to uphold the human and labour rights of migrant domestic workers, but also to avoid tensions between countries.

To this end, ASEAN member states signed the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers on 13 January 2007 (ASEAN, 2007a). The Declaration calls upon both the labour sending and the labour receiving countries of Southeast Asia to set up an effective mechanism to safeguard the rights of migrant workers. Following this, on 13 July 2007, the ASEAN Committee on the Implementation of the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers (ACMW) was established to ensure the effective implementation of the commitments made under the Declaration.

The ACMW was also tasked with facilitating the development of the legally binding ASEAN Framework Instrument on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers (ASEAN, 2007b). Of note is the involvement of civil society in the drafting process: the Task Force on ASEAN Migrant Workers (TF-AMW) – a grouping made up of key regional and national civil society organisations; trade unions; human rights and migrant rights NGOs; and migrant worker associations – submitted a proposal to the ACMW in 2009. The proposal notes that the ASEAN Framework Instrument should accord special attention to migrant domestic workers. It is argued that they are a particularly vulnerable group due to their unique working environment: they are in private homes where they live and work in isolation.

The TF-AMW (2009:111) proposal states that ASEAN member states should ‘recognise, in law and practice, domestic work (household work) as work, and accord migrant domestic workers the protection of the law as provided in international labour and human rights standards’. The proposal also highlights the necessity of addressing ‘the specific needs of women migrant domestic workers’, which would include ‘the right to integrity of their body and soul, free from all forms of physical, psychological, and sexual violence in their workplace and residence; the right to obtain reproductive health services and the right to obtain aid, assistance, and empowerment when they experience violence’ (TF-AMW, 2009:111).

The ACMW is still in the process of finalising the Framework Instrument which it hopes will serve as a blueprint for the harmonisation of national labour laws and policies on migrant workers in ASEAN member states. It is hoped that member states would adopt the Framework Instrument before 2015, when a single regional economic market known as the ASEAN Economic Community would be established.

^ To the top

Conclusion

This NTS Insight, in its discussion of the policy responses to the Domestic Workers Convention 2011 in Southeast Asia, has observed that while labour sending countries are supportive of the Convention, labour receiving countries have been more wary of embracing it as it is a legally binding treaty. However, as the phenomenon of migrant domestic workers is a transnational one, some form of international standard is necessary to protect these workers from abuse and exploitation.

The Convention thus presents an opportunity for countries to revisit their employment laws and to ensure that it guarantees protection to migrant domestic workers. This is essential for labour receiving countries such as Malaysia and Singapore as their reputation as an attractive labour destination may well become tarnished if their legislative protection for such workers continues to lag behind international best practices. As nations that depend on a steady inflow of migrant domestic workers to support their economic progress, they cannot afford to neglect the issue for long.

To effectively address the issue of migrant domestic workers, a comprehensive regional approach involving collaboration among labour sending and receiving countries would be needed. ASEAN is well positioned to lead efforts to establish common standards for the region. Member states have already signed the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers. The next step is to make this Declaration legally binding. To this end, the ASEAN Framework Instrument on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of the Migrant Workers, which would be legally binding on both labour sending and labour receiving countries, is currently being developed. When finalised, the Framework Instrument would serve as a blueprint for countries in the region to introduce complementary laws and policies on migrant domestic workers.

^ To the top

References

ASEAN,

2007a, ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers, Cebu, Philippines, 13 January. http://www.aseansec.org/19264.htm

2007b, Statement of the establishment of the ASEAN Committee on the Implementation of the ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers, Manila, 30 July. http://www.asean.org/20768.htm

Battistella, Graziano and Maruja M.B. Asis, 2011, Protecting Filipino transnational domestic workers: Government regulations and their outcomes, PIDS Discussion Paper Series No. 2011-12, Makati City: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS). http://dirp4.pids.gov.ph/ris/dps/pidsdps1112.pdf

Chok, Stephanie, 2011, ‘One day off a week – Domestic workers share their views’, The Online Citizen, 6 July. http://theonlinecitizen.com/2011/07/one-day-off-a-week-%E2%80%93-domestic-workers-share-their-views/

Dato’ Hj. Abdul Hamid, Bahiyah, 2009, ‘The identity construction of women/maids in domestic help for hire discourse in selected Malaysian newspapers’, European Journal of Social Sciences,Vol. 9, No. 1. http://www.eurojournals.com/ejss_9_1_15.pdf

Dioquino, Rose-An Jessica, 2011, ‘DOLE seeks support for Domestic Workers Convention’, GMA News Online, 12 October. http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/235177/pinoyabroad/dole-seeks-support-for-domestic-workers-convention

‘Employer’s cruelty main cause of maids crime’, 2012, Emirates247, 19 February. http://www.emirates247.com/crime/local/employer-s-cruelty-main-cause-of-maids-crime-2012-02-19-1.443655

‘Govt trying to introduce “live-out” system for domestic helpers abroad’, 2011, Antara News, 21 November. http://www.antaranews.com/en/news/77809/govt-trying-to-introduce-live-out-system-for-domestic-helpers-abroad

‘Gulf’s domestic workers unfairly represented in media’, 2011, Migrant Rights, 18 December. http://www.migrant-rights.org/2011/12/18/gulfs-domestic-workers-unfairly-represented-in-media/

Hangzo, Pau Khan Khup, Zbigniew Dumienski and Alistair D.B. Cook, 2011, ‘Legal protection for Southeast Asian migrant domestic workers: Why it matters’, NTS Insight, May, Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies. http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/rsis/nts/HTML-Newsletter/Insight/NTS-Insight-may-1101.html

Heng, Russell, 2011, ‘NGO calls for international domestic workers law to be ratified in Singapore’, The Online Citizen, 17 June 2011. http://theonlinecitizen.com/2011/06/ngo-calls-for-international-domestic-workers-law-to-be-ratified-in-singapore/

Hodal, Kate, 2011, ‘Singapore maids to be spared English and cooking test’, Guardian, 6 December. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/06/singapore-maids-english-cooking-test

‘Indonesia, Malaysia at odds on measures to boost maids’ welfare’, 2012, Jakarta Globe, 19 March. http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/seasia/indonesia-malaysia-at-odds-on-measures-to-boost-maids-welfare/505679

‘Indonesians vent anger over maid abuse in Malaysia’, 2010, Channel NewsAsia, 22 September. http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/afp_asiapacific/view/1082737/1/.html

International Labour Organization (ILO),

2011a, ‘100th ILO annual Conference decides to bring an estimated 53 to 100 million domestic workers worldwide under the realm of labour standards’, Press release, 16 June. http://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/100thSession/media-centre/press-releases/WCMS_157891/lang--en/index.htm

2011b, Decent work for domestic workers: Convention 189 & Recommendation 201 at a glance, Geneva: International Labour Office. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_170438.pdf

2011c, ‘Statement by H.E. Dr Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, President of the Republic of Indonesia, at the 100th International Labour Conference’, 14 June. http://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/100thSession/media-centre/speeches/WCMS_157638/lang--en/index.htm

2011d, Decent work for domestic workers, ILC.100/IV/2A, Geneva: International Labour Office. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_151864.pdf

Kesavan, Ragunath, 2009, ‘Press release: State intervention needed for domestic workers’, The Malaysian Bar, 8 July. http://www.malaysianbar.org.my/press_statements/press_release_state_intervention_needed_for_domestic_workers.html

Lin, Wenjian, 2011, ‘Sections of controversial maid blog now private’, Straits Times Indonesia, 8 December. http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/international/sections-of-controversial-maid-blog-now-private/483422

‘Migrant domestic workers in the Middle East: Exploited, abused and ignored’, 2010, Migrant Rights, 30 April. http://www.migrant-rights.org/2010/04/30/migrant-domestic-workers-in-the-middle-east-exploited-abused-and-ignored/

Ministry of Manpower, Singapore (MOM), 2011, ‘Mandatory Settling-In Programme to replace English entry test’, Press release, 4 December. http://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/Pages/PressReleasesDetail.aspx?listid=399

Ng, Esther, 2012, ‘Mandatory weekly rest days for foreign domestic workers from 2013’, Today Online, 7 March. http://www.todayonline.com/Singapore/EDC120305-0000171/Mandatory-weekly-rest-days-for-foreign-domestic-workers-from-2013

Philippines,

1995, Republic Act No. 8042: Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995. http://www.poea.gov.ph/rules/ra8042.html

2011, Resolution No. 615, Fifteenth Congress of the Republic of the Philippines, Second Regular Session, 4 October. http://www.senate.gov.ph/lisdata/1224110328!.pdf

Ramirez-Machado, José Maria, 2003, Domestic work, conditions of work and employment: A legal perspective,Conditions of work and employment series No. 7, Geneva: International Labour Office. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_travail_pub_7.pdf

‘RI-Malaysia MoU fails to provide needed safeguards for migrant workers’, 2011, The Jakarta Post, 1 June. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2011/06/01/ri-malaysia-mou-fails-provide-needed-safeguards-migrant-workers.html

Soeriaatmadja, Wahyudi, 2012, ‘Jakarta plans to stop sending maids by 2017’, The Straits Times, 5 January. http://www.asianewsnet.net/home/news.php?id=25885&sec=1

Tan, Amanda, 2012, ‘Expect longer wait for Indonesian maids’, The Strait Times, 1 March. http://www.menafn.com/qn_news_story.asp?StoryId=%7B6b8e9186-28fb-4a21-95c5-c19b329c3129%7D&src=MWHEAD

Task Force on ASEAN Migrant Workers (TF-AMW), 2009, Civil society proposal: ASEAN Framework Instrument on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers, Singapore. http://www.workersconnection.org/resources/Resources_72/book_tf-amw_feb2010.pdf

UN Development Fund for Women – Singapore National Committee (UNIFEM Singapore), Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) and Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), 2011, Made to work: Attitudes towards granting regular days off to migrant domestic workers in Singapore, Singapore. http://unwomen-nc.org.sg/uploads/Day%20Off%202011%20June%2022.pdf

^ To the top |