|

THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE US ANTI-HUMAN TRAFFICKING STRATEGY FOR NATIONAL POLICIES: THE CASE OF MALAYSIA.

By Manpavan Kaur

The annual US Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report has become the primary international enforcement mechanism against human trafficking. This NTS Alert discusses the role played by this mechanism, and critically analyses its effectiveness in combating human trafficking and influencing national policies. The case of Malaysia is used to assess the impact of this US strategy on national policies. One shortcoming of the strategy is highlighted: it prioritises prosecution rates of traffickers over the rights protection of those trafficked, thereby creating a human security deficit in responding to human trafficking.

|

|

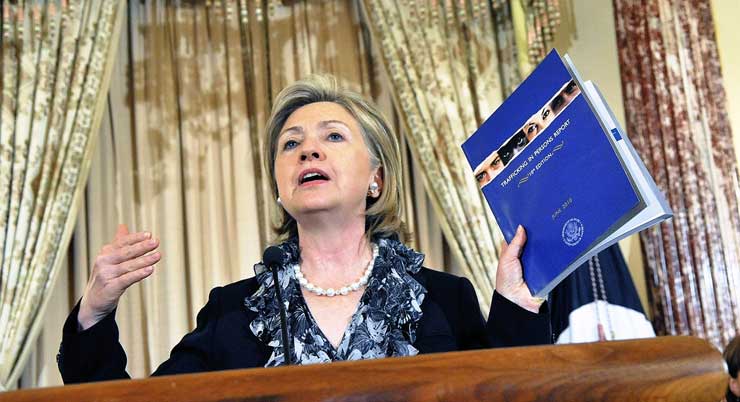

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announcing the release of the US Trafficking in Persons Report 2010.

Credit: US Department of State. |

Contents:

Recommended Citation: Kaur, Manpavan, 2011, ‘The Implications of the US Anti-Human Trafficking Strategy for National Policies: The Case of Malaysia’, NTS Alert, August (Issue 1), Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies for NTS-Asia.

| |

Introduction

Human trafficking as defined by the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (UN Trafficking Protocol) is an international crime involving the trans-border or intra-state movement of persons by the use of force, coercion, deception or abuse of power or position of vulnerability, thereby negating or diminishing the persons’ consent and resulting in their exchange for the purpose of their exploitation (UN, 2000).

Human trafficking has entered the international security lexicon as a non-traditional security (NTS) issue. NTS issues are transnational in nature, endangering both state and non-state actors, and therefore multi-state cooperation is needed to effectively tackle human trafficking (Emmers, 2004). Although human trafficking is tackled as an international security issue, the worldwide momentum for legislation on human trafficking was sparked by concern for the human security of those trafficked. For example, the impetus for the UN Trafficking Protocol was Argentina’s championing of the issue of child trafficking. Debilitating socioeconomic, cultural and political conditions such as poverty, discrimination, violence and political instability are some of the causes of the human insecurity experienced by those who are trafficked, and these circumstances leave them vulnerable to exploitation. Effective prevention of human trafficking thus requires the observance and enforcement of international human rights standards for the protection of trafficked persons (Chuang, 2006:473).

Unfortunately, there were concerns within the international community that a purely human rights perspective would be insufficient to combat human trafficking and that human trafficking needed to be part of a broader international security approach based also on tackling the predicament as a transnational organised crime (Gallagher, 2001:982; Chuang, 2006:471). The result of negotiations at the international community level was that the relevant human rights were not comprehensively included in the UN Trafficking Protocol but have been encapsulated in the UN General Assembly’s 2002 Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking. Furthermore, it appears that dominant anti-human trafficking strategies, such as the US Trafficking in Persons (TIP) enforcement strategy, in prioritising criminal and immigration control measures have lost sight of protecting the human rights of trafficked persons.

The UN Trafficking Protocol does not have any mechanism to enforce the implementation of its provisions and this leaves the Protocol powerless to demand the compliance of states parties (Hendrix, 2010:182). In recognition of this gap, the US instituted a global anti-human trafficking enforcement strategy undertaken by its Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, and advanced through its annual TIP Report. Overall, this enforcement strategy has proven to be the most successful internationally in achieving a rise in the implementation of anti-human trafficking measures by states. It has led to increases in arrests and convictions of traffickers, and the establishment and implementation of regulations, culminating in significant progress at the international level in curbing the proliferation of human trafficking (Tiefenbrun, 2007:280).

Countries have been responsive to the US strategy largely because of the threat of economic sanctions (Hendrix, 2010:193). Consequently, while Southeast Asia has a low ratification rate of the UN Trafficking Protocol, the monitoring and categorisation conducted under the US TIP enforcement strategy has been influential in pressurising states to develop domestic mechanisms to address human trafficking (Caballero-Anthony and Hangzo, 2010: Table 2; Chuang, 2006). Table 1 shows some of these domestic mechanisms.

The US has, therefore, through the TIP Report, assumed a global enforcement role in the area of human trafficking. In the following sections, the effectiveness of the US anti-human trafficking strategy in combating human trafficking and influencing national policies will be critically analysed. To that end, the case of Malaysia will be used.1

|

Table 1: Summary of anti-human trafficking laws in Southeast Asia.

|

Country |

Legislation |

Nature of penalty |

Brunei Darussalam |

Trafficking and Smuggling of Persons Order (2004) |

Imprisonment – 4 to 30 years

Fine

Caning |

Cambodia |

Law on Suppression of Human Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation (2007) |

Imprisonment – 1 year to life

Fine |

Indonesia |

Elimination of the Crime of Human Trafficking (2007) |

Imprisonment – 3 to 15 years

Fine |

Lao PDR |

No specific human trafficking law – relies on the Penal Code |

Imprisonment – 5 years to life

Fine |

Malaysia |

Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants Act (2007, amended in 2010) |

Imprisonment – 3 to 20 years

Fine

Caning |

Myanmar |

Anti-Trafficking in Persons Law

(2005) |

Imprisonment – 3 years to life; or death penalty

Fine |

Philippines |

Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act

(2003) |

Imprisonment – 1 year to life

Fine |

Singapore |

No specific human trafficking law – relies on a variety of domestic laws |

Imprisonment

Fine

Caning |

Thailand |

Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act B.E. 2551 (2008) |

Imprisonment – 6 months to 15 years

Fine |

Timor-Leste |

No specific human trafficking law – relies on the Penal Code |

Imprisonment – 4 to 25 years |

Vietnam |

No specific human trafficking law – relies on the Penal Code (but the Law on Prevention and Suppression against Human Trafficking was passed in early 2011, and will come into force in 2012.) |

Imprisonment – 2 to 20 years

Fine |

Source: Compiled by Pau Khan Khup Hangzo and Manpavan Kaur.

|

^ To the top

The US TIP Report as a Global Anti-Human Trafficking Strategy

International legislation on human trafficking developed alongside legal developments within the US. The US was among the drafters of the UN Trafficking Protocol introduced into the Vienna process for negotiating international law on transnational organised crime in 1999 (Friedrich et al., 2006:5). Coincidently, in 1998, the Clinton Administration had issued a Directive to establish an anti-human trafficking strategy based on prevention, protection and prosecution (3Ps strategy), one similar to that used in the UN Trafficking Protocol (Miko and Park, 2002:8). Subsequently, the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), part of the broader Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, was enacted in October 2000; and the UN Trafficking Protocol was adopted in November that year (Chuang, 2006:2).

Recognising that the transnational nature of human trafficking requires concerted action by origin, transit and destination countries, the TVPA extends beyond US jurisdiction to influence anti-human trafficking policies abroad. This extra-jurisdictional approach has been employed since the US State Department under President George W. Bush issued its first congressionally mandated report on worldwide human trafficking in 2001, and is derived from an established US tradition of congressional oversight over the actions of other countries in politically important areas (Gallagher, 2010:2). Direct precedents are the International Narcotics Control Strategy Report issued annually since 1987 and the International Religious Freedom Report issued annually since 1999 (Gallagher, 2010:2).

The TVPA’s Minimum Standards

While it is not the world’s first anti-human trafficking law, the TVPA is comprehensive, and in mandating the TIP Report, is the only assessment tool to tie governments’ anti-human trafficking efforts to economic sanctions (Chuang, 2006:439, 442; Friedrich et al., 2006:5). The TIP Report assesses countries, and records their tier position, based on their adherence to the ‘minimum standards’ specified in Section 108 of the TVPA (Box 2; see Table 3 for tier classifications). While all forms of human trafficking are deemed serious, the TVPA places a specific emphasis on sex trafficking and forced labour by categorising them as ‘severe’ forms of human trafficking (Box 1).

Box 1: Definition of ‘severe’ forms of human trafficking.

Section 103(8) of the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2000 (TVPA) states that the term ‘severe forms of trafficking in persons’ means:

- sex trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age; or

- the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.

Source: US (2000). |

Box 2: Minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking.

Section 108(a) of the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2000 (TVPA) specifies ‘minimum standards’ for the elimination of trafficking:

- The government of the country should prohibit severe forms of trafficking in persons and punish acts of such trafficking.

- The government of the country should prescribe punishment commensurate with that for grave crimes, such as forcible sexual assault for the knowing commission of any act of sex trafficking involving force, fraud, coercion, or in which the victim of sex trafficking is a child incapable of giving meaningful consent, or of trafficking which includes rape or kidnapping or which causes a death.

- The government of the country should prescribe punishment that is sufficiently stringent to deter and that adequately reflects the heinous nature of the offense, where there is the knowing commission of any act of a severe form of trafficking in persons.

- The government of the country should make serious and sustained efforts to eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons.

Source: US (2000). |

The 3Ps Strategy

Incorporated into the assessment of the minimum standards – specifically, under Section 108(a)(4) of the TVPA – is the 3Ps strategy (see Box 3). In principle, there is no order of priority among the 3Ps, which underlines that the prosecution and prevention of human trafficking as a transnational organised crime needs to be conducted in tandem with the protection of trafficked victims to further a comprehensive human security approach. However, in practice, the cooperation of trafficked victims in the prosecution of traffickers is a prerequisite to government protection from destination countries, as seen in the case of Malaysia that is discussed in this NTS Alert (Mattar, 2003:165–7; Lopiccolo, 2009:865).

Box 3: The 3Ps strategy.

Section 108(b) of the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2000 (TVPA) states that, in determining whether countries have made serious and sustained efforts to eliminate the severe forms of trafficking in persons specified under Section 108(a)(4), the following factors should be taken into account:

- Whether the government of the country vigorously investigates and prosecutes acts of severe forms of trafficking in persons that take place wholly or partly within the territory of the country.

- Whether the government of the country protects victims of severe forms of trafficking in persons and encourages their assistance in the investigation and prosecution of such trafficking, including provisions for legal alternatives to their removal to countries in which they would face retribution or hardship, and ensures that victims are not inappropriately incarcerated, fined, or otherwise penalized solely for unlawful acts as a direct result of being trafficked.

- Whether the government of the country has adopted measures to prevent severe forms of trafficking in persons, such as measures to inform and educate the public, including potential victims, about the causes and consequences of severe forms of trafficking in persons.

Note: bold added.

Source: US (2000). |

Imposition of Economic Sanctions

Countries which do not meet the TVPA’s minimum standards would be assessed as falling into Tier 3; and subject to economic sanctions and foreign pressure (see Table 3 for tier classifications; Hendrix, 2010:193). Sanctions constitute the punitive component of the US TIP enforcement strategy, one which infringes on state sovereignty (Hendrix, 2010:195, Chuang, 2006:459–60). Specifically, the sanctions regime is based on the withdrawal, by the US President, of non-trade-related, non-humanitarian financial assistance from countries deemed not sufficiently compliant with the TVPA’s minimum standards (Hendrix, 2010:196). The withholding of such assistance can also be achieved through US foreign diplomatic influence on international financial institutions and development banks such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (Hendrix, 2010:196; Chuang, 2006:453–4).

|

Table 2: US sanctions on Southeast Asian countries placed in Tier 3.

|

Year |

Sanctions |

Full |

Partial |

Waived |

2003 |

Myanmar |

- |

- |

2004 |

Myanmar |

- |

- |

2005 |

Myanmar |

Cambodia |

- |

2006 |

Myanmar |

- |

- |

2007 |

Myanmar |

- |

Malaysia |

2008 |

Myanmar |

- |

- |

2009 |

- |

Myanmar |

Malaysia |

2010 |

- |

Myanmar |

- |

2011 |

- |

Myanmar |

- |

|

Table 2 lists the Southeast Asian countries which have been placed in Tier 3 over the last nine years, and thus considered for sanctions. They include Myanmar, Cambodia and Malaysia. However, Malaysia is the only destination country in the region to be categorised as Tier 3. It is also the only country to have had sanctions waived.

The variation in whether sanctions are imposed arises from at least two considerations. First, generally, there is a reluctance to implement economic sanctions because such actions have adverse impacts on the wider population when their main purpose is to push governments into compliance with the TVPA’s minimum standards (Mattar, 2003:172–3). Therefore, sanctions could be waived in the ‘national interest’ of the Tier 3 country.

Second, the concern that sanctions could undermine cooperation with the US also comes into play. States that are subject to sanctions could become defensive and unwilling to acknowledge the claims within the US TIP Report; they might instead view the US anti-human trafficking enforcement strategy as a hegemonic imposition on their countries (Mattar, 2003:172–3). Therefore, the US prefers to engage with countries, giving credit to countries that respond to the TIP Report with significant efforts towards compliance although these may yet be far from fulfilling the TVPA’s minimum standards (Chuang, 2006:454). This may be why sanctions were waived in the case of Malaysia, but not Myanmar (a non-responsive regime) (Gallagher, 2010:9).

In the following section, a critical analysis of the effect of the US TIP enforcement regime will be undertaken with particular reference to Malaysia’s anti-human trafficking policies and protection efforts.

^ To the top

The US TIP Enforcement Strategy and Malaysia’s Policy Responses

The TIP Report has classified Malaysia as a destination and transit country for men, women and children in the forced-labour and sex industries. Over the last five years, Malaysia has been fluctuating between Tier 2 Watch List and Tier 3 (see Table 3 for classification criteria). The 2011 TIP Report placed Malaysia in the Tier 2 Watch List because it had not made enough efforts towards effective, improved and consistent implementation of its anti-human trafficking legislation, and protections for those trafficked. While the report commented on the lack of effective victim care and counselling by the authorities, its main focus was Malaysia’s deficiency in effective investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases, and its failure to address the problems of government complicity in human trafficking (US Department of State, 2011a). In the following, the influence of the TIP Report on Malaysia’s anti-human trafficking policies is analysed, and several shortcomings of the US TIP enforcement strategy highlighted.

|

Table 3: US Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report – tier classifications.

|

Tier |

Classification Criteria |

| 1 |

Fully comply with the US Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2000 (TVPA) minimum standards. |

| 2 |

Do not yet fully comply with the TVPA’s minimum standards but are making significant efforts to do so. |

| 2 Watch List |

Do not yet fully comply with the TVPA’s minimum standards but are making significant efforts to do so,

and

- the absolute number of victims of severe forms of trafficking is very significant or is significantly increasing.

- there is a failure to provide evidence of increasing efforts to combat severe forms of trafficking in persons from the previous year.

or

- the determination that a country is making significant efforts to bring itself into compliance with the TVPA’s minimum standards was based on commitments by the country to take additional future steps over the next year.

|

| 3 |

Do not fully comply with the TVPA’s minimum standards and are not making significant efforts to comply. Countries will be subject to sanctions if they do not bring themselves into compliance within 90 days, unless sanctions are waived by a Presidential decree. |

Source: US Department of State (2011c).

|

Enacting Anti-Human Trafficking Legislation

The broader US anti-human trafficking enforcement strategy comprises economic and social assistance to countries for the enactment, enforcement and strengthening of relevant national legislation and victim assistance programmes (Tiefenbrun, 2007:279). Accordingly, countries have been responsive to feedback in the TIP Report and have utilised US support and funding to establish their anti-human trafficking infrastructure. Malaysia’s primary legislation in this regard is the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act passed in 2007. The Act was amended in 2010 to include smuggling of migrants. This conflation of human trafficking and smuggling within the law is problematic as these are deemed as two distinct issues in international law (Chacon, 2006:2985–7). It is thus of concern that the TIP Report does not specifically address this distinction (Gallagher, 2010:4–5).

According to legal practitioners in Malaysia, the 2010 amendment broadens Malaysian laws for prosecuting illegal migration crimes but has adverse implications for the protection of trafficked persons.2 A Malaysian government official noted that the failure to distinguish between trafficked and smuggled persons risks denying protection status to trafficked persons, and exposes them to the risk of criminal prosecution should they be wrongly identified as consenting smuggled migrants.3

Implementing Anti-Human Trafficking Measures – Institutional Infrastructures

In Malaysia, the Council for Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants (MAPO) – established under the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act 2007 as a sub-agency of Malaysia’s Ministry of Home Affairs – bears central responsibility for tackling human trafficking within the country.

MAPO has, however, been criticised for its narrowly defined mandate, which is to ensure that Malaysia is internationally accredited as being free of illegal activities in connection with the human trafficking and smuggling of migrants (MAPO, n.d.). Hence, MAPO concentrates solely on arrests and convictions. Consequently, local non-governmental organisations (NGOs), expressing concern over the lack of inter-agency collaboration, observed that this narrow approach has inhibited effective cooperation.4 This is particularly since the US TIP enforcement strategy advocates multisectoral approaches on the basis that such approaches are better able to address the complexities inherent in irregular migration.

There was a consensus among NGOs, legal practitioners and human rights advocates interviewed in Malaysia that the failure of the US TIP Report to provide a detailed analysis of the effectiveness of MAPO (including the lack of inter-agency and multisectoral efforts), has led to a narrow governmental approach focused on the criminalisation of actors involved in human trafficking activities.5

Promoting Protection Measures

The US TIP enforcement strategy, in placing a low priority on assessing countries’ measures for the protection of human rights, is not encouraging of a comprehensive agenda that takes into account the rights protection of trafficked persons. Indicative of this approach is the absence, within the TVPA’s minimum standards, of an independent list of standards for the protection of the human rights of trafficked persons (Chuang, 2006:471). Accordingly, the US approach departs from the purpose of the UN Trafficking Protocol. While the purpose of the Protocol is to combat the trafficking of persons and protect victims of human trafficking, with full respect for their human rights, the TVPA focuses on just and effective punishment of traffickers (Enck, 2003:376).

Nevertheless, the US TIP enforcement strategy promotes the international human rights of trafficked persons through its recognition that they often cannot return to their home communities due to social stigma or the risk of reprisals by their traffickers. Accordingly, the US TIP enforcement strategy upholds the right of trafficked persons to gain permission to stay in destination countries. The TVPA encourages the provision of temporary or even permanent residency status in destination countries. This has precipitated the institution of temporary stay for trafficked persons in destination countries. Such status is however contingent upon cooperation with law enforcement in prosecution efforts (Chuang, 2006:451; see also earlier discussion in the subsection discussing the 3Ps strategy). This is based on a model law derived from the UN Trafficking Protocol and the TVPA, and issued by the US State Department in 2003, which states that anti-human trafficking laws ‘shall provide victims of trafficking … with appropriate visas or other required authorisation to permit them to remain in the country for the duration of the criminal prosecution against the traffickers’ (Tiefenbrun, 2007:277).

In Malaysia, this is implemented through interim protection orders, which are essentially temporary visas allowing trafficked persons to stay in government-gazetted shelters for the duration of the investigation and prosecution. These visas are, as highlighted by legal practitioners and a government official in Malaysia, conditional on the involvement and cooperation of those trafficked in prosecutions, in line with the country’s emphasis on prosecution rates.6 Although this period is legally stipulated as two weeks, it tends to extend to three to six weeks (Malaysia, 2007: Article 44). Thereafter, according to information from a government official, the courts may, upon confirmation that a person is a victim of human trafficking, grant a protection order extending the individual’s stay at a shelter to three months, diverting him or her to counselling and rehabilitative programmes.7

^ To the top

Concluding Observations

This NTS Alert has critically analysed the influence and nature of the US TIP Reports, with particular focus on Malaysia’s national anti-human trafficking policies. The analysis revealed a human rights deficit in national anti-human trafficking policies arising from the US TIP enforcement strategy’s emphasis on protection measures for trafficked persons being conditional on their assistance and cooperation in identifying and prosecuting traffickers in destination countries (US Department of State, 2011b). As a result of that emphasis, the strategy does not offer any support for the development of a comprehensive agenda that encompasses the protection of trafficked persons’ rights.

Furthermore, governments develop their anti-human trafficking policies based entirely on what they perceive to be the expectations of the US TIP Report (Chuang, 2006:490). In their quest to adhere to the prescriptions of the US TIP enforcement mechanism, countries fail to assess domestic needs and implement context-specific anti-human trafficking measures. Moreover, the prima facie criminal and immigration law approach encouraged by the US, with its emphasis on securing prosecutions, has led to countries such as Malaysia strengthening their border controls in an effort to curb irregular migration. This exacerbates the human trafficking problem because stricter border controls compel migrants to seek the assistance of smugglers, and if this extends into exploitation, they become cases of human trafficking (Shinkle, 2007:2).

This issue of the NTS Alert has focused on the human rights deficit within anti-human trafficking measures and the inadequate policy responses at the national level. The next issue of this month’s NTS Alert series will discuss the internal issues arising from these gaps and their implications, including the rise of NGO activities.

^ To the top

Notes

- This NTS Alert relies on material accumulated during a research trip to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, between 13 and 17 June 2011. The material is used as contextual evidence alongside scholarly writing on the themes discussed in the NTS Alert. During the research trip, qualitative research on the dynamics of human trafficking in Malaysia was conducted through open-ended interviews and observational interaction. A cross-section of views was solicited, from non-partisan organisations, and government and non-governmental agencies. All interviews were conducted in confidentiality, and the names of interviewees are withheld by mutual agreement.

- Personal interviews with practitioners in the non-governmental sector, Kuala Lumpur, 13 and 14 June 2011.

- Personal interview with expert on Malaysian national human rights issues, Kuala Lumpur, 14 June 2011.

- Personal interviews with representatives from NGOs, Kuala Lumpur, 13 June 2011.

- Personal interviews with (1) expert on Malaysian national human rights issues, Kuala Lumpur, 14 June 2011; (2) NGO practitioner, Kuala Lumpur, 13 June 2011; (3) NGO practitioner, Kuala Lumpur, 14 June 2011.

- Personal interviews with (1) a government official with work experience at shelters for trafficked victims, Kuala Lumpur, 16 June 2011; (2) a notable legal specialist, Kuala Lumpur, 13 June 2011.

- Personal interview with a government official with work experience at shelters for trafficked victims, Kuala Lumpur, 16 June 2011.

^ To the top

References

Caballero-Anthony, Mely and Pau Khan Khup Hangzo, 2010, ‘Responding to Transnational Organised Crime: Case Study of Human Trafficking and Drug Trafficking’, NTS Alert, July (Issue 2), Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies for NTS-Asia. http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/rsis/nts/html-newsletter/alert/NTS-alert-jul-1002.html

Chacon, Jennifer M., 2006, ‘Misery and Myopia: Understanding the Failures of U.S. Efforts To Stop Human Trafficking’, Fordham Law Review, Vol. 74, No. 6, pp. 2977–3040. http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4173&context=flr&sei-redir=1#search=%22Chacon%2C%20Jennifer%20M.%2C%202006%2C%20%C3%A2%C2%80%C2%98Misery%20Myopia%3A%20Understanding%20Failures%20U.S.%20Efforts%20Stop%20Human%20Trafficking%C3%A2%C2%80%C2%99%22

Chuang, Janie A., 2006, ‘The United States as Global Sheriff: Using Unilateral Sanctions To Combat Human Trafficking’, Michigan Journal of International Law, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 437–94. http://ssrn.com/abstract=990098

Council for Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants. See Majlis Antipemerdagangan Orang dan Antipenyeludupan Migran (MAPO).

Emmers, Ralf, 2004, Globalization and Non-traditional Security Issues: A Study of Human and Drug Trafficking in East Asia, Working Paper No. 62, Singapore: Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies. http://dr.ntu.edu.sg/bitstream/handle/10220/4461/RSIS-WORKPAPER_66.pdf?sequence=1

Enck, Jennifer L., 2003, ‘The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime: Is It All That It Is Cracked Up To Be? Problems Posed by the Russian Mafia in the Trafficking of Humans’, Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce, Vol. 30, pp. 369–94. https://litigation-essentials.lexisnexis.com/webcd/app?action=DocumentDisplay&crawlid=1&srctype=smi&srcid=3B15&doctype=cite&docid=30+Syracuse+J.+Int'l+L.+%26+Com.+369&key=4c3f26b83891aba1e24500b76e2f40ed

Friedrich, Amy G., Anna N. Meyer and Deborah G. Perlman, 2006, The Trafficking in Persons Report: Strengthening a Diplomatic Tool, UCLA School of Public Affairs. http://www.spa.ucla.edu/ps/research/J-Traffic06.pdf

Gallagher, Anne T.,

2001, ‘Human Rights and the New UN Protocols on Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling: A Preliminary Analysis’, Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 975–1004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2001.0049

2010, ‘Improving the Effectiveness of the International Law of Human Trafficking: A Vision for the Future of the US Trafficking in Persons Reports’, Human Rights Review, Vol. 12. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1735581

Hendrix, Mary Catherine, 2010, ‘Enforcing the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act in Emerging Markets: The Challenge of Affecting Change in India and China’, Cornell International Law Journal, Vol. 43, pp. 173–205. http://www.lawschool.cornell.edu/research/ILJ/upload/Hendrix.pdf

Lopiccolo, Julie Marie, 2009, ‘Where Are the Victims? The New Trafficking Victims Protection Act’s Triumphs and Failures in Identifying and Protecting Victims of Human Trafficking’, Whittier Law Review, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 851–85.

Majlis Antipemerdagangan Orang dan Antipenyeludupan Migran (MAPO), n.d., ‘About Mapo’. http://mapo.bernama.com/mapo.php

Malaysia, 2007, Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act 2007, Act 670 Laws of Malaysia, Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad. http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/population/trafficking/malaysia.traf.07.pdf

Mattar, Mohamed Y., 2003, ‘Monitoring the Status of Severe Forms of Trafficking in Foreign Countries: Sanctions Mandated under the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act’, Brown Journal of World Affairs, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 159–78. http://www.protectionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Monitoring-the-Status-of-Severe-Forms-of-Trafficking-in-Foreign-Countries.pdf

Miko, Francis T. and Grace (Jea-Hyun) Park, 2002, ‘Trafficking in Women and Children: The U.S. and International Response’, Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, 18 March. http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/9107.pdf

Shinkle, Whitney, 2007, Protecting Trafficking Victims: Inadequate Measures?, Transatlantic Perspectives on Migration, Policy Brief No. 2, Institute for the Study of International Migration, Georgetown University. http://www12.georgetown.edu/sfs/isim/Publications/GMF%20Materials/TVPRA.pdf

Tiefenbrun, Susan W., 2007, ‘Updating the Domestic and International Impact of the U.S. Victims of Trafficking Protection Act of 2000: Does Law Deter Crime?’, Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, Vol. 38, pp. 249–80. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1020214

UN, 2000, Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime. http://www.uncjin.org/Documents/Conventions/dcatoc/final_documents_2/convention_%20traff_eng.pdf

UN General Assembly, 2002, Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights and Human Trafficking, Report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to the Economic and Social Council, New York: UN Economic and Social Council. http://www.unhchr.ch/huridocda/huridoca.nsf/e06a5300f90fa0238025668700518ca4/caf3deb2b05d4f35c1256bf30051a003/$FILE/N0240168.pdf

US, 2000, Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, Public Law 106-386, 28 October. http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/10492.pdf

US Department of State,

2011a, 2011 Trafficking in Persons Report – Malaysia. http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/topic,4565c22532,4565c25f425,4e12ee633c,0.html

2011b, ‘Moving toward a Decade of Delivery – Protection’. http://www.state.gov/g/tip/rls/tiprpt/2011/166774.htm

2011c, ‘Tier Placements’, Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. http://www.state.gov/g/tip/rls/tiprpt/2011/164228.htm

^ To the top

|