NTS Alert August 2010

DEMOGRAPHIC ‘TIME BOMB’ OR DEMOGRAPHIC ‘DIVIDEND’: MYTHS SURROUNDING AGEING POPULATIONS IN ASIA

This Alert examines the validity of three common concerns associated with growing ageing populations. The first concern addresses predictions made about rising health care costs due to bigger numbers of older persons in society. The second concern addresses warnings about rising pension costs and the third concern addresses the claim of intergenerational solidarity decreasing in the Asian context, where the notion of filial piety is being called into question. Specifically, these concerns are explored within the Japanese, Singaporean and Thai context, with the aim of clarifying whether growing ageing populations in Asia are a demographic ‘time bomb’ or a demographic ‘dividend’.

|

|

| Credit: whitecat singapore, flickr.com |

Introduction

According to the 2009 HSBC ‘The Future of Retirement’ report, the world’s ageing population will increase from 550 million today to 1.4 billion by 2050. Such a big number directly conjures up images of panic in the minds of many; policymakers in particular often emphasise the increase in health care and pension costs because of the projected growing number of persons above the age of 65. The growing ageing population continues to be framed as a ‘burden’ on society and their increase in numbers as a ‘crisis’. This narrative has existed in western Europe, the United States and Japan since the 1980s (Guillemard, 1985; Heller et al., 1986; and OECD 1988a, b and c). However, it is increasingly relevant in Asia, where South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, have joined the group of developed economies which are now facing consistently falling fertility rates and bigger ageing populations. Population giants China and India are also paying more attention to elder care and are worried about the economic and social consequences of ageing.

In Southeast Asia, emerging economies are anticipating an ageing population. For example, Malaysia projects that it will reach 'ageing nation status' by 2035. Ms Halijah Yahaya, Welfare Department Deputy Director-General recently stated (Malaysia Likely to Reach Ageing Nation Status by 2035, 2010): ‘In 2000, the number of elderly people was 1.45 million or 6.2 per cent of the total population but in 2009, the number increased to 2.03 million or 7.1 per cent of the total population’.

But what do these numbers really say? Is there a real need to worry that ageing populations are a big ‘burden’ alongside global concerns such as climate change and economic recessions? It may appear strange to couple climate change with ageing; however the Secretary-General of the International Actuarial Association, Mr Yves Guerard, stated in February 2010 at a pensions industry conference in Singapore: ‘[The ageing issue is] a big, immediate urgent problem ... I will compare that with climate change. We prefer not to believe in that because it’s inconvenient’ (Ageing Asia Problem ‘Urgent’, 2010).

This Alert aims to dispel some of the myths around ageing populations, arguing that there is no ‘crisis’ and that rather than being a ‘burden’, the increase in older persons is a ‘demographic dividend’ (HSBC, 2009), providing potential for higher productivity and wealth creation, rather than causing an uncontrollably high increase in public fiscal expenditure. Three areas of concern typically associated with growing ageing populations centre around increased pension costs, health care costs and growing intergenerational tensions. This Alert will summarise some of the developments that have occurred in Japan, Singapore and Thailand, in an effort to analyse whether Asia is facing a demographic ‘time bomb’ (Mullan, 2002), or a demographic ‘dividend’ which our societies can gain from rather than suffer under. Demographic policy trends from Japan, Singapore and Thailand have been chosen as illustrations for the following reasons:

- Japan has a bigger percentage of its population that is ageing compared to other Asian countries and is the earliest country in the region to deal with this issue. According to the Japanese Government’s Statistical Handbook, the population of persons 65 years and older was 28.22 million in 2008; meaning 22.1 per cent of the total population are 65 years and older. Japan’s elderly population rose from 7.1 per cent in 1970 to 14 per cent in 1995. Like most countries, there are more older women in Japan than men. Japan is at a different stage than other countries in the region and can offer some effective lessons, particularly in the area of maintaining health care costs.

- Singapore is a developed city-state, but faced the situation of having a higher percentage of its population in the ageing category later than Japan. It is now in the Asian limelight for the policies it is implementing, particularly in the area of labour policies which are allowing Singaporeans to work beyond the official retirement age, if they wish. In the Government’s ‘State of the Elderly 2009’ report, it is stated that Singapore’s ageing population – comprising persons over 65 years of age – number 330,100. The aging population figure has risen from 2.5 per cent of the population in 1965 to 8.7 per cent in 2009. The sex ratio of the older population is 795 males per 1,000 females.

- Thailand is less developed than Japan and Singapore and has a lot more infrastructure related challenges, particularly because of its wide urban-rural divide. Thailand’s total population as of 2009 is 69 million. About 11.5 per cent of this population is 60 years or older (approximately 7.8 million) according to the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat in World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision. Like Japan and Singapore, Thailand also has a larger female than male ageing population. Compared to some of its other Southeast Asian neighbours, Thailand has been a lot more proactive in trying to implement a range of policies for its rapidly ageing population.

^ To the top

Concern No. 1: Health Care Costs will Become Uncontrollably High because of the Predicted Increase in Ageing Populations

One of the major concerns constantly mentioned in connection with ageing populations is that health care costs will keep on rising in proportion to the increased number of older persons in society. However, once this statement is broken down into its parts, i.e., what type of health care, at what age and in which country, the alarmist concerns surrounding it become largely unwarranted. In addition, it is important to remember that today’s ageing populations, particularly in Asia, are healthier and living longer than ever before. Thais, for example, have increasingly been reporting that their health is ‘good’ or ‘very good’. In 1994, 38 per cent of Thais reported they were in good health; this figure rose to 47 per cent in 2007 (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2007):

By 2050, close to 80 per cent of all deaths are expected to occur in people older than 60. Health expenditure increases with age and is concentrated in the last years of life – but the older a person dies, the less costs are concentrated in that period. Postponing the age of death through healthy ageing combined with appropriate end-of-life policies could lead to major health care savings.

Tiziana Leone from the London School of Economics also wrote in her recent article, ‘How can Demography Inform Health Policy?’ (2010), that predictions of health care costs associated with ageing have been ‘overstated’ and that usually they are balanced out by the ‘postponement of death-related hospital costs, later in life’.

The two most significant areas of health care important for ageing populations are the quality of primary health care, in order to recognise the onset of chronic diseases early on; and the affordability of long-term care (LTC), especially when the older person in question is on his/her own (Beard, 2010). Japan has shown that both can be done effectively while maintaining lower health costs. It decided to implement LTC because of the following reasons: (1) the ageing of caregivers themselves, such as spouses and children; (2) the declining ratio of older persons living with their children, particularly in urban settings; (3) a shortage of care workers and nursing homes; and (4) an increase of women in the labour force – women who no longer want to subscribe to ‘old fashioned’ ideas of filial piety (Ihara, 1998).

^ To the top

Japan

In his forthcoming paper ‘Financing Health Care in a Rapidly Aging Japan’, Dr Naoki Ikegami (2010) writes that Japan implemented LTC in 2000 and finds it to be ‘manageable and affordable’. He also writes that since the onus is on the government to set the specific eligibility criteria, LTC is easier to estimate and budget. The eligibility criteria and services provided in Japan for LTC include the following:

- Everyone who is 65 years and older, as well as individuals between the ages of 40 and 64 with an age related disability are eligible, based on a ‘physical and mental disability assessment test’ (Chen, 2005).

- Benefits are all in the form of services and are provided either institutionally or via the community (Chen, 2005).

- In a community setting, individuals are assisted by a care manager who helps to create a care plan; giving guidance on services and providers (Chen, 2005).

- The following information applies to Japanese health insurance in general and not just long-term care insurance (LTCI). The premium for elders aged 75 and over is now the same within prefectures. Co-payment is the same nationwide at 30 per cent for the 90 per cent who have incomes below that of the average worker and 30 per cent for those with incomes above that. For LTCI, the premium levels are set by each municipality. However in two-thirds of the municipalities, the average levels are in the range of 4,000 Yen plus or minus 500 Yen per month (Ikegami, 2010).

LTC services in Japan include the following: assistance in activities of daily living (ADL), such as dressing and eating; assistance in instrumental ADL (IADL), such as meal preparation, cleaning, shopping and management of medication; home modifications, such as installing ramps, handrails, and emergency alert systems; and transportation to and from adult day-care centers and health care facilities. Services provided by physicians are generally not included, except when the physician is employed by the institution. – Professor Naomi Ikegami

|

In the case of Japan, the eligibility criteria are for individuals who require light care, and 16 per cent of the elderly population is currently covered (Campbell, 2010). According to Ikegami, costs can be kept low by not covering all services. ‘Limited resources tend to be presented as a life-or-death issue, but not so in LTC’, says Ikegami (forthcoming). This is where much can be decided with the eligibility criteria. In addition, Ikegami also writes that since more and more deaths will occur after the age of 75, fewer older persons will choose aggressive treatment options, resulting in lower costs.

On a macro level, Japan has a two-tiered system for containing overall health expenditures. First, the Prime Minister decides on the overall fee schedule, which is a guideline on how much costs – for example, medical procedures – can be raised or lowered across the board. Second, the Health Ministry’s Central Social Insurance Council provides guidelines on price revisions for individual procedures, such as MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scan fees – which were reduced by 30 per cent in the 2002 cost-setting process, from US$ 160 to US$ 110 (Ikegami, 2010). Dr John Creighton Campbell commented in a 2009 interview with The New York Times (Arnquist, 2009):

Japan is particularly adept at manipulating prices to keep costs down. Every two years the price of each treatment, test, medication and device is examined to see if excess profits are leading to overuse, in which case the price is cut. When the government wants to increase some service, such as home visits by physicians, it increases the price. Constant, detailed attention to prices has helped Japan keep the growth rate of health care spending down to 1 to 3 per cent a year despite rapid aging.

Japan currently spends 8.1 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health, ranking it 19th among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Ikegami, 2010). Important lessons can be learned from the Japanese example which aims to keep costs low for health care, yet provides a good level of care.

^ To the top

Singapore

In Singapore, the situation is quite different. Health care costs for the government are manageable. However, individuals who need health care coverage the most, such as low-income older women who have never participated in the formal labour force, often go uncovered. Singapore citizens and Permanent Residents who are employed are covered by MediShield[1] till the age of 85 (Asher and Nandy, 2008).

Once enrolled in MediShield, individuals are automatically enrolled into an additional health insurance programme for LTC called ElderShield at age 40. ElderShield was started in 2002 with the explicit goal of providing coverage for the elderly who are ‘severely disabled’, i.e., the elderly that are ‘unable to do at least 3 of these 6 activities of daily living – washing, dressing, feeding, toileting, mobility, and transferring’ (Ministry of Health, n.d.). Once enrolled at age 40, the yearly premium for a policyholder is S$ 146 per year up to the age of 65. Medisave[2] can be used to pay for this premium. After 65, the individual in question is covered for life. If the individual covered by ElderShield applies for LTC, he/she has to go through an assessment process – similar to the one in Japan – in order to receive the benefits. The benefits consist of monthly cash payments of S$ 300 per month for 60 months (ElderShield 300) or S$ 400 for 72 months (ElderShield 400) to ‘help pay the out-of-pocket expenses for the care of the severely disabled person’ (Ministry of Health, n.d.). Singapore also provides special training for caregivers, whether they are family members or not.

There are two types of nursing homes in Singapore, the Volunteer Welfare Organisation (VWO) nursing homes and private nursing homes. VWO homes are more often government-subsidised and have stringent admission criteria. For example, the Lions Home for the Elderly lists the following criteria:

- Must be a Singapore citizen or Permanent Resident with household income per capita of S$ 1,300 or less.

- Applicants who are sick (especially the elderly sick) with medical conditions must be semi-ambulant, wheel-chair bound or bed bound.

- Applicant’s level of care must fall within categories 3 and 4 of the Ministry’s Resident Assessment Form, and require a high dependence level of nursing care.

- Applicant does not have close relatives or caregivers to provide support or care.

- Applicants with psychological and psychiatric illnesses must not have suicidal or violent tendencies.

Government-funded nursing homes follow a fee structure determined by the Ministry of Health. The Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) helps with information provision on ADL and retirement homes, and aids with placement in a retirement home if needed. Subsidies for government nursing home fees are provided based on family income or means testing. For example, for a family of four with a total combined income of less than S$ 1,440, a 75 per cent subsidy is provided. However, if a family’s (family of four) combined income is more than S$ 5,600, no subsidy is provided (Agency for Integrated Care, n.d.). It is tough to gain admission into a government-subsidised nursing home and private nursing homes are considerably more expensive. A typical monthly fee in a private nursing home is S$ 1,300 and it becomes more expensive if ground floor occupation is sought. With long waiting lists in government-subsidised nursing homes and higher fees in private nursing homes, some older persons may find that they are not covered for LTC, as ElderShield cash payouts may not be enough. Dr Angelique Chan, Director of the Tsao Foundation and Ageing Research Initiative in Singapore, recently commented (2010):

The government realises that [Eldershield] is insufficient and that it does not pay out for enough time. For example, an older woman with a hip fracture who needs 10 years of help, would need assistance for a longer time and the open question of who will step in and fill the gap, remains’.

^ To the top

Thailand

In Thailand, LTC coverage is the least developed. However, the government is making an effort. Community based pilot programmes are currently being tested, engaging volunteers in part-time elder care. However, the problem with volunteers is that they cannot be there 24/7 taking care of a person who needs genuine LTC. The Japan and Singapore examples show that health care costs for ageing populations can be manageable and affordable, especially when the majority of older persons are living longer and healthier lives. In Thailand, for example, 88 per cent of respondents to the 2007 Survey on Older Persons reported that they manage daily living activities on their own, without needing assistance (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008). Less than 4 per cent cited that they have difficulties with eating, bathing, dressing or using the toilet (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008).

This is not to say that containing health care costs for good primary health care and LTC programmes is not challenging, as is shown in Singapore and Thailand. However, it is also not the big financial ‘burden’ that it is made out to be and a fairly small segment of the ageing population needs genuine LTC. In addition, if the gap between initial treatment in a hospital setting and rehabilitation services by community health care workers, particularly in Singapore, is narrowed, older persons with chronic diseases will be able to manage their health better and it will not have exaggerated cost implications for policymakers (Chan, 2010). Many older persons are also caregivers themselves, which will be addressed in section three (Concern No. 3) of this Alert.

^ To the top

Concern No. 2: Policymakers Seriously Worry about National Pension Schemes as the Increasing Ageing Population will be a Big Financial Burden

Another major concern often associated with growing ageing populations is the increasing ‘financial burden’ of inadequate pension systems. It is often debated whether both the current and future ageing generations will be adequately covered. Unfortunately, older persons are often portrayed as not wanting to work when they reach post-retirement-age and are no longer seen as productive and positive contributors to society. However, this is often not the case. Three of the most overlooked factors when it comes to the reform of pension systems are:

- The dependency ratio is often misinterpreted, making the growing number of older persons seem like more of a financial burden.

- In the Asian context in particular, older persons often want to work beyond the retirement age. It should be noted, however, that this occurs largely in advanced economies with a large formal sector and a choice of higher-level job opportunities. It is a different picture for countries in Asia, such as Thailand, where more of the elderly work in the informal sector, in agriculture, are self-employed or are in physically demanding jobs.

- More women need to be engaged in the workforce, by reform in childcare and maternity leave policies.

^ To the top

The Singapore Central Provident Fund (CPF)

Before discussing the above-mentioned issues in greater detail, it is important to know how some of the pension systems in the region function. In Singapore, the Central Provident Fund (CPF) started in 1955 as a social security system. It is managed by the Ministry of Manpower and is based on individual, mandatory contributions by both employers and employees (Hu, 2009). The contribution is based on the worker’s salary and there are three categories of workers: (1) private sector employees; (2) pensionable government employees; and (3) non-pensionable government employees. A slightly lower contribution is mandated when an individual is between the ages of 50 and 55 and only one-third of regular contributions is mandated when an individual is between the ages of 60 and 65. For instance, if an individual makes S$ 45,000 per annum, the CPF contribution is S$ 1,553 (S$ 653 by the employer and S$ 900 by the employee) if he/she is below the age of 35 or between 35 and 45 years of age. If this individual is between 50 and 55 years old, the contribution is S$ 1,283 (S$ 473 by the employer and S$ 810 by the employee). If the individual is between the ages of 60 and 65, the contribution is S$ 563 (S$ 226 by the employer and S$ 337 by the employee). To see how CPF contributions are calculated, click here.

|

Table 1: CPF contributions as a percentage of salaries for private sector and non-pensionable government employees (with effect from September 2010).

Age

(Years) |

Contribution |

Employer’s Share

(% of wage) |

Employee’s Share

(% of wage) |

Total

(% of wage) |

35 and below |

15 |

20 |

35 |

Above 35 – 45 |

15 |

20 |

35 |

Above 45 – 50 |

15 |

20 |

35 |

Above 50 – 55 |

11 |

18 |

29 |

Above 55 – 60 |

8 |

12.5 |

20.5 |

Above 60 – 65 |

5.5 |

7.5 |

13 |

Above 65 |

5.5 |

5 |

1 |

Source: Central Provident Fund Board |

|

Table 2: CPF contributions as a percentage of salaries for pensionable government employees.

Age

(Years) |

Contribution |

Employer’s Share

(% of wage) |

Employee’s Share

(% of wage) |

Total

(% of wage) |

35 and below |

11.25 |

15 |

26.25 |

Above 35 – 45 |

11.25 |

15 |

26.25 |

Above 45 – 50 |

11.25 |

15 |

26.25 |

Above 50 – 55 |

8.25 |

13.5 |

21.75 |

Above 55 – 60 |

6 |

9.375 |

15.375 |

Above 60 – 65 |

4.125 |

5.625 |

9.75 |

Above 65 |

4.125 |

3.75 |

7.875 |

Source: Central Provident Fund Board |

The CPF is broken down into three different savings accounts for individuals below the age of 55: (1) the Ordinary Account (OA), which ‘could be used to purchase homes and insurance, support education and other expenses’ (Hu, 2009); (2) the Special Account (SA) which is mainly for retirement savings; and (3) the Medisave Account, which is for ‘medical and critical illness insurance’ (Hu, 2009). If the government invests on behalf of the contributors, a 2.5 per cent interest can be earned from the OA and a 4 per cent interest on the other two accounts (Hu, 2009). Withdrawal from CPF accounts by members can occur from as early as the age of 55. However, there has been much debate over this issue. In addition, there has also been criticism of the fact that most of the CPF savings are tied to housing investment, potentially making Singaporeans ‘asset rich, cash poor’ (McCarthy, Mitchell and Piggott, 2002). Professor Mukul Asher has also said of the Singapore pension system as early as 1999:

Singapore’s retirement system consists of state-mandated and state-managed individual retirement accounts. While the Central Provident Fund (CPF) is administering well its housekeeping functions, there is little transparency in its investment function and the return on investment has been poor. At the end of 1996, the majority of its assets were invested in non-marketable government bonds, issued specifically to the CPF Board to meet their interest obligations. The interest on these bonds is identical with the average of short-term deposit rates of four local banks. For the last decade, the effective real rate of return on the bonds has been close to zero. The money raised from issuing bonds to the CPF Board is invested by the Singapore Government Investment Corporation. Its portfolio and investment performance are not made publicly available. Thus, CPF members do not know the ultimate deployment of their funds.

In order to increase the amount of savings for Singapore and to overcome the ‘asset rich, cash poor’ problem associated with housing, the Singapore Government introduced the CPF LIFE scheme this year, which sets aside a portion of cash savings in the Retirement Account (set up at age 55) as the premium for annuity. This scheme has four different plans: the Life Balanced Plan, the Life Basic Plan, the Life Income Plan and the Life Plus Plan. This scheme is ‘expected to provide lifelong income for elderly in their retirement’ (Hu, 2009). For additional information on this scheme please click here.

The Old Age Dependency Ratio

The old age dependency ratio, which is often used as an indicator in both popular media and academic literature to make predictions about the different kinds of financial ‘burdens’ ageing populations will be causing, is the ratio of older persons to the working age population (Leone, 2010). It is usually calculated by dividing the population aged 0–14 (or 0–19) plus the population aged over 60 or 65, by the remaining population (Leone, 2010). Phil Mullan writes in his book The Imaginary Time Bomb that dependency ratio calculations are not a good indicator of the so-called ‘burden’ caused by ageing populations, as they do not account for unforeseen baby booms, changes in unemployment or labour force participation (2002). Mullan (2002: 123) comments:

Trends in the old age dependency ratio do not give any guide to what will happen to the real ‘burden’ on future working population [sic] ... most demographic projections are bound to mislead because they ignore changes in unemployment and labour force participation rates over the period of projections, usually 50 years.

For example, if there were six individuals of working age and two older persons, the old age dependency ratio would be 3. This ratio presupposes that all six individuals of working age are indeed working and productive, and that the two older persons are not working and therefore ‘dependent’. In a second example, there may be four individuals of working age and four older persons, which results in a ratio of 1. However, the four working persons cited in the second example may be much more productive than the six individuals of working age cited in the first example. In addition, other dependents, such as ‘children, the unemployed and the economically inactive’ (Mullan, 2005) are completely ignored in this old age dependency ratio calculation.

The HSBC 2009 ‘The Future of Retirement’ report conducted a global survey with 15,000 respondents and found that, if given a choice, 45 per cent of respondents in Singapore and 52 per cent of respondents in South Korea would like to work beyond the official retirement age. This goes against the widespread view that once an individual is considered a part of the older population, it is not possible to be a productive member of the national economy and regarded as a positive contributor.

In Singapore, the request to work longer is being addressed with a new policy implementation called ‘The Tripartite Guidelines on Re-Employment of Older Employees’. This policy is supposed to be implemented by 2012 and enacts legislation that allows Singaporeans to be re-hired between the ages of 62 (current official retirement age) and 65. The Ministry of Manpower (2010) has described the eligibility of older individuals for re-employment in its guidelines as follows:

Employers should aim to re-employ the majority of their older employees. As a good practice, employers should offer re-employment contracts to all employees who are medically fit to continue working and whose performance is assessed to be satisfactory or above.

Guidelines are also provided for the types of wages, medical benefits and leave entitlement to be granted to re-employed workers. A survey conducted by Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower in November 2009 also shows that companies are more willing to hire older workers now. Out of 3,200 companies surveyed, more than three out of five stated that they would be open to hiring workers older than 62 years of age. For more information, please click here.

The main point in this pension discussion is that it is not necessarily demographic trends that are the deciding factor when it comes to changes in the economy or wealth creation (Mullan, 2002). Additional economic and social factors play a large role as well and often go unnoticed. Aside from the ‘re-employment’ of older workers (in the case of Singapore), most countries in Asia still have not been able to engage more women into the workforce successfully, due largely to the lack of adequate childcare and maternity leave policies. This fact directly feeds into the distortion of the dependency ratio. Mullan (2002: 127) elaborates:

Over the past quarter century female participation rates have been rising, contributing to the economy’s productive output. Most would agree that some link exists between more working women and falling fertility. Hence the same trend of falling birth rates which boosts the aged dependency ratio is also related to the increase in economic activity rates by women thereby boosting the size of the economic cake from which dependents share. If more employment was available, especially of an adequate quality and linked to childcare facilities, it is doubtless the case that even more women would work. Once again it is the case that economic and social factors play a more decisive role than demographic trends in determining the scale of national wealth, part of which provides for dependents.

Mullan also points out that economic growth over time is an important factor that largely goes unnoticed when projecting costs for the so-called rapidly ageing population. Citing Great Britain as an example, he writes that in the year 1900, Britain’s overall spending on education, health and social security amounted to 3 per cent of the GDP. In the 1950s, it was 12 per cent, and in the early 2000s the figure was 22 per cent (Mullan, 2005). Simultaneously, the level of productivity quadrupled during these years. Based on this pattern, Mullan (2005) states: ‘It has not been a question of working out how to ‘afford’ ageing, but of using the gains of greater prosperity in what (until recently) were widely recognised as progressive and civilised ways of organising for society’s collective benefit’.

There are many contextual differences between a developed country such as Singapore, and a developing country such as Thailand. For example, raising the retirement age in Thailand would not make much of a difference, because the majority of the population is self-employed or works in the agricultural sector and most individuals tend to work beyond the age of 60 (the official retirement age) regardless (Knodel, 8 July 2010). In addition, Thailand has a large informal sector and cites big differences in infrastructure in its rural versus urban settings.

^ To the top

Thailand’s Pension Funds

Thailand used to only have a pension fund for civil servants and state employees. It was reformed in 1997, renamed the Government Pension Fund, with details of its contribution system more specific than the former one. In 1999, the Old Age Pension Fund was established as part of the Social Security System that was launched in 1991 to cover formal employment in the private sector. It significantly increased coverage and mandated contributions not just from the government and the state, but also from employees and employers in the private sector. The first pension-type payment of this fund will only go out in 2014 as members have to have contributed for at least 15 years, although those who retire before are entitled to a lump sum payment (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008). The Thai government, besides currently trying to expand retirement coverage to include the informal sector, has a universal elderly welfare allowance of 500 Baht per month. This allowance does not make much of a difference in the urban setting. However it does in rural areas (Knodel, 8 July 2010).

With a gradual increase in pension coverage, the younger generation, which is better educated and employed in jobs that provide retirement coverage, will be better covered in the future and would not be paying for the ‘financial burden’ of the growing ageing population. In another survey conducted in Thailand in 2007 covering persons aged 18–59, it was found that 58 per cent of respondents in the 25–29 age group are currently in employment that has an associated retirement benefit scheme. The same applies to 38 per cent of individuals in the 35–39 age group and 17 per cent in the 55–59 age group.

^ To the top

Concern No. 3: Intergenerational Tension will Increase and Break Down Family Solidarity because of Growing Ageing Populations

The third concern about growing ageing populations most often seen in the popular media, and mentioned among policymakers and some academics is that intergenerational tension will increase and intergenerational solidarity will decline as family structures break down, with the Asian notion of ‘filial piety’ being followed less and less (Wijaya, 2009; and Westley, 1998). In addition, with increasing rates of migration in countries such as Thailand, where children are often living away from their parents, there have been numerous reports of reduced filial responsibility and even desertion of parents by children.

However, such reports are typically based on selective anecdotal reports and ignore systematic evidence to the contrary. Professor John Knodel (8 July 2010), of the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan, emphasised that it really depends on how intergenerational solidarity is defined and viewed. For example, if it is being stated in the Thai media that children are providing less and less economic support to their parents (The Nation, 2007), the 2006 Migration Impact Survey (MIS) and the series of large-scale representative National Surveys on Older Persons in Thailand contradict these statements, as results in Table 3 below show. Knodel and Chayovan (2008) recently wrote:

Children are often important sources of economic support to elderly parents, providing money and goods … This contradicts impressions promoted in the Thai media that ‘an increasing number [of elderly] do not get support from their younger relatives’ (The Nation 2007).

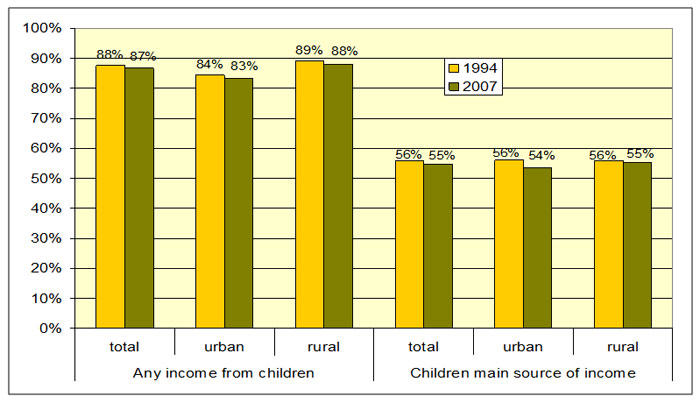

Table 3: Percentage of parents aged 60 and over who reported children provided income during the prior year (1994 and 2007) in Thailand.

Source: 1994 and 2007 Surveys of Older Persons in Thailand (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008); and ‘Is Intergenerational Solidarity Really on the Decline? Cautionary Evidence from Thailand’ (Knodel, 2009). |

In addition, social contact between parents and their children is much better than one may imagine as Table 4 indicates. Attitudes of older persons are also tolerant of new forms of social contact facilitated by technological advances, particularly with the widespread availability of cell phones. Over 80 per cent of older Thais surveyed in the MIS agreed with the statement: ‘Children who live far away do not need to visit frequently if they often call their parents on the phone’ (Knodel et al., 2010).

|

Table 4: Contact between parents and non-co-resident children during the past year, Thailand, 2007.

Among elderly with at least one non-co-resident child, percentage of whom during past year had: |

Total |

Type of area |

| Urban |

Rural |

| Visits from a non-co-resident child |

Daily or almost daily |

24.2 |

19.6 |

25.8 |

At least weekly |

37.8 |

36.1 |

38.4 |

At least monthly |

55.9 |

61.0 |

54.2 |

At least once during year |

84.0 |

86.6 |

83.1 |

| Telephone contact with a non-co-resident child |

Daily or almost daily |

12.0 |

16.3 |

10.6 |

At least weekly |

34.5 |

45.2 |

30.7 |

At least monthly |

63.8 |

73.4 |

60.4 |

At least once during the year |

68.8 |

77.8 |

65.7 |

Source: 2007 Survey of Older Persons in Thailand (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008); and ‘Is Intergenerational Solidarity Really on the Decline? Cautionary Evidence from Thailand’ (Knodel, 2009).

|

It is important to recognise that parents and their adult children are unlikely to stand by passively and allow their situation and relationships deteriorate as the social, economic and technological environment around them changes. Rather, they will exercise human agency to minimise negative impacts and maximise potential benefits thus leading to changes in forms but not necessarily functions of intergenerational support and solidarity. – John Knodel |

In Singapore, there is similar evidence that intergenerational solidarity and family relations between older persons and the younger generation is not on the decline, or at least not as rapidly as is often assumed. A recent article in the local newspaper, TODAY (Leong, 2010), described older persons more as caregivers, rather than being the individuals who need care themselves. Professor Sarah Harper, Head of the Oxford Institute of Ageing, which as a part of a Global Ageing Survey, had 1,000 respondents from Singapore, commented that people assume older persons to be dependants, however she added: ‘But in actual fact, when we look at families, we see older people making large contributions...helping their children around the home’ (Leong, 2010). In Thailand, grandparents are even more likely to take care of grandchildren, because of high migration rates, causing the ‘skip generation’ phenomena (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008). The ‘skip generation’ situation refers to grandparents who live with their grandchildren with no middle generation present due for example to migration (Knodel and Chayovan, 2008). 1,500 Singaporeans were also polled this year for the ‘Families Value Survey’, conducted by the National Family Council. Results showed that 87 per cent of persons surveyed would not consider placing their parents in nursing homes and saw it as a duty to take care of their parents (Kor, 2010).

Table 5: Singapore policies relating to intergenerational support.

Parent/handicapped Parent Relief: For taxpayers who are supporting, and staying together with, their or their spouses’ parents, grandparents and great grandparents, they may claim up to S$ 5,000, or up to S$ 8,000 should the parents be handicapped (dependent on eligibility criteria). For taxpayers who are not staying with them, they may claim up to S$ 3,500 or up to S$ 6,500 for handicapped parents/grandparents.

Grandparent Caregiver Tax Relief: Working mothers whose child is being cared for by his or her grandparents will be eligible for a Grandparent Caregiver Tax Relief of S$ 3,000. This applies to working mothers of Singapore Citizen children aged 12 years and below as of 1 Jan 2004.

The Maintenance of Parents Act: Passed in 1995 as a preventive policy to ensure that children provide financial support to their aged parents.

The Multi-Tier Family Housing Scheme: Encourages co-residence by giving priority allocation for public housing to extended-family applications.

The Joint Selection Scheme: Encourages close-proximity living, by allowing parents and married children to have priority in selecting separate public flats in the same estate. Benefits of this scheme and the Multi-Tier Family Housing Scheme also include the option to pay a lesser amount of a commitment deposit and a more attractive mortgage loan package.

The CPF (Central Provident Fund) Housing Grant: Grant is available to married first-time applicants where they will be eligible for a S$ 30,000 to S$ 40,000 housing grant if they buy a resale flat from the open market near their parents’ house, defined as within the same town or within 2 km of their parents’ house. |

Source: ‘The Dynamics of Multigenerational Care in Singapore’ (Thang and Mehta, 2009) |

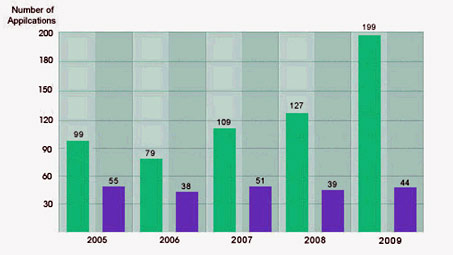

The latest policy debate in Singapore concerns amending the Maintenance of Parents Act and strengthening it to enable ‘elderly parents to approach a legal tribunal for help if their children refuse to support them financially’ (Basu, 2010). The idea for such a law on filial piety was first tabled in 1994 and has been re-tabled this year. A Tribunal for the Maintenance of Parents, which has three members (a President and two other members), already exists and hears cases related to this Act. On the Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports (MCYS) website (n.d.), it is stated that the Tribunal ‘adopts a non-adversarial stance and refers the differences between the parties to a conciliation officer for mediation before applications are heard’. Most applicants tend to be widowers, widows or divorcees (Mathi, 1999). In each case, the Tribunal President tends to look at ‘each child’s average income, his circumstances, the parent’s monthly needs and the parent-child relationship’ (Mathi, 1999). Table 6 summarises how many applications the tribunal received from 2005–2009.

Table 6: Number of applications for Maintenance and for Variation of Maintenance Orders (2005–2009)

Legend:

Legend:

Green bar: Number of new applications

Purple bar: Number of applications for variations (changes)

Source: Tribunal for the Maintenance of Parents |

According to these accounts, intergenerational solidarity is not on the decline as much as people may assume. Chan (2010) recently emphasised: ‘The more important issue for the incoming group of older persons is emotional support and family cohesiveness’. Family structures are also more solid than may be portrayed. However, debate around the issue of filial piety remains and the sudden surge in applications to the Tribunal for the Maintenance of Parents in 2009 needs to be analysed.

^ To the top

Conclusion

Taking a deeper look at recent surveys conducted in the region on issues related to ageing, specifically health care costs, pension benefits and intergenerational solidarity, it can be stated that health care costs for the increasing ageing populations will be more affordable than we think, that older persons are healthier than ever before, that older persons in the region want to work beyond the retirement age in larger numbers than assumed, that intergenerational solidarity is hardly on the decline, and that older persons are contributing to their families and societies in more positive ways than ever.

Increasingly, older adults will be better educated and have more resources. They will have better health behaviours over their life course and thus live longer, healthier lives. This should enhance their ability to work and live independently in older age, thus lessening the pressure placed on the family to provide old age care. Future cohorts of older people may prefer to live alone. – ‘The Ageing of Singapore’, Angelique Chan, 2009. |

However, this does not mean that there are no areas of concern for ageing populations that require further research and a more coordinated policy response. The three areas most significant for the Southeast Asian context seem to be the following:

- With every decade, there are fewer numbers of living children per elderly person. Thanks to more modern communication means and continued support from family members, it is not a demographic trend that one has to immediately be concerned about. However, some challenging consequences will have to be dealt with, as future older persons face the situation of being alone, especially as employment related migration of adult children increases.

- LTC will remain a challenge in the health care realm. Once there are not enough family members who can assist or if the older person in question cannot afford assisted living care, how will he/she cope with frailty or chronic illness?

- The rural/urban divide in developing countries in Southeast Asia leads to three main differences between rural and urban areas: (1) transport, which affects access to good health care; (2) education – older persons in urban areas tend to be better educated and, therefore, have more of a grasp of which benefits (whether it be pension coverage or health care) to access and the methods of access; and (3) the larger migration rates of children from rural areas to urban areas or other countries.

^ To the top

Endnotes

- MediShield is a low-cost catastrophic illness insurance scheme. Introduced in 1990, the Singapore Government designed MediShield to help members meet medical expenses from major illnesses which could not be sufficiently covered by their Medisave balance. MediShield operates on a co-payment and deductible system to avoid problems associated with first dollar, comprehensive insurance (Central Provident Fund, Singapore. http://mycpf.cpf.gov.sg/Members/home.htm).

- Medisave was introduced in 1984 as a national medical savings account system for Singaporeans. The system allows Singaporeans to set aside a portion of their income in a Medisave account to meet future personal or immediate family members’ hospitalisation and day surgery. It also pays for certain outpatient expenses (Central Provident Fund, Singapore. http://mycpf.cpf.gov.sg/Members/home.htm).

^ To the top

References

‘Ageing Asia Problem “Urgent”’, 2010, The Straits Times/AFP, 1 February, online edition. http://www.straitstimes.com/BreakingNews/Asia/Story/STIStory_484927.html

Agency for Integrated Care, n.d., Home page, http://www.aic.sg/faq/faq-nursing-homes/

Asher, Mukul and Amarendy Nandy, 2008, ‘Singapore's Policy Responses to Ageing, Inequality and Poverty: An Assessment', International Security Review, Vol. 61, Issue 1.

Arnquist, Sara, 2009, ‘Health Care Abroad: Japan’, The New York Times, 25 August, online edition. http://prescriptions.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/25/health-care-abroad-japan/

Basu, Radha, 2010, ‘More Bite for “Filial Piety” Law’, The Straits Times, 11 March, online edition. http://www.straitstimes.com/BreakingNews/Singapore/Story/STIStory_500666.html

Beard, John, World Health Organization (WHO), Telephone interview on 9 July 2010.

Campbell, John Creighton, Ikegami Naoki, and Mary Jo Gibson, 2010, ‘Lessons from Public Long-Term Care Insurance in Germany and Japan’, Health Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 87–95, online edition. http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/29/1/87

Chan, Angelique, 2009, ‘The Ageing of Singapore’, Ageing in East Asia: Challenges and Policies for the Twenty-first Century, London: Routledge.

Chan, Angelique, Interview on 23 July 2010.

Chen, Chen-Fen, 2005, The Long-Term Care Policies in Germany, Japan and Canada: A Lesson for Taiwan, National Chung-Cheng University, online edition. http://swat.org.tw/downloads/journal/050102.pdf

Central Provident Fund Board, n.d. http://mycpf.cpf.gov.sg/Members/home.htm

Dodge, Brooks, 2008, ‘Primary Healthcare for Older People: A Participatory Study in 5 Asian Countries,’ HelpAge International, online edition. http://www.helpage.org/Resources/Researchreports/main_content/MHcl/Primaryhealthcare.pdf

Furedi, Frank, 1997, Population and Development: A Critical Introduction, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Guillemard, Anne-Marie, 1985, ‘The Social Dynamics of Early Withdrawal from the Labour Force in France’, Ageing and Society, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 381–412.

Heller, P., Richard Hemming, and Peter W. Kohnert, 1986, ‘Ageing and Social Expenditure in the Major Industrialised Countries 1980–2025’, Occasional Paper 47, Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Hu, Qiuyi, 2009, ‘Financial Security Policies on Population Ageing: A Comparison between Japan and Singapore’, Paper presented at the Economic Development and Social Changes in ASEAN in the Face of the Global Financial Crisis Conference, online edition. http://www.waseda.jp/gsaps/gp/project2008/pdf/international2008_hayashi3.pdf

HSBC, 2009, ‘The Future of Retirement’, online edition. http://www.hsbc.com/1/2/retirement/interactive-report

Ihara, Kazuhito, 1998, Japan’s Policies on Long-Term Care for the Aged: The Gold Plan and the Long-Term Care Insurance Program, International Longevity Center, online edition. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/APCITY/UNPAN023659.pdf

Ikegami, Naoki, Forthcoming, ‘Financing Health Care in a Rapidly Ageing Japan’. Provided via e-mail on 8 July 2010.

Ikegami, Naoki, Telephone interview on 8 July 2010.

Knodel, John, 2009, ‘Is Intergenerational Solidarity Really On The Decline? Cautionary Evidence from Thailand’, Paper presented at a seminar on Family Support Networks and Population Ageing, 3–4 June, in Qatar, online edition. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:DzVsmH_DgzYJ:www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/groups/events_calendar/public/Doha/Knodel%2520Doha%2520seminar%2520paper%2520revised%25205_24.doc+Is+Intergenerational+Solidarity+Really+On+The+Decline%3F+Cautionary+Evidence+from+Thailand%E2%80%99&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk

Knodel, John and Napaporn Chayovan, 2008, Population Ageing and the Well-being of Older Persons in Thailand: Past Trends, Current Situation and Future Challenges, Population Studies Center Research Report 08-659, Thailand, online edition. http://www.globalaging.org/health/world/2008/thailand.pdf

Knodel, John, Jiraporn Kespichayawattana, Chanpen Saengtienchai et al., 2010, ‘How Left Behind are Rural Parents of Migrant Children? Evidence from Thailand’, Ageing and Society, Vol. 30, pp. 811–41, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Knodel, John, Telephone interview on 8 July 2010.

Kok, Melissa and Melissa Sim, 2010, ‘Firms to Keep Older Workers’, The Straits Times, 27 April, online edition. http://www.straitstimes.com/BreakingNews/Singapore/Story/STIStory_519596.html

Kor, Kian Beng, 2010, ‘80% Support Family Values’, The Straits Times, 26 June, online edition. http://www.straitstimes.com/BreakingNews/Singapore/Story/STIStory_546126.html

Leone, Tiziana, 2010, ‘How can Demography Inform Health Policy?’, Health, Economics, Policy and Law, Vol. 5, Issue 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, online edition. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayFulltext?type=1&fid=6851224&jid=HEP&volumeId=5&issueId=01&aid=6851216

Leong, Wee Keat, 2010, ‘More Grandparents Lending Helping Hand’, TODAY, 30 April.

‘Malaysia Likely to Reach Ageing Nation Status by 2035’, 2010, Bernama, 27 April, online edition. http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2010/4/27/nation/20100427160245&sec=nation

Mathi, Braema, 1999, ‘Over 400 Parents Compel Children to Support Them’, The Sunday Times, 4 April, online edition. http://www.singapore-window.org/sw99/90404st.htm

McCarthy, D., O.S. Mitchel and I. Piggot, 2002, ‘Asset Rich and Cash Poor: Retirement Provision and Housing Policy in Singapore’, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, Vol. 1, No. 3.

Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports (MCYS), Singapore, n.d., Page on Tribunal for the Maintenance of Parents. http://app1.mcys.gov.sg/AboutMCYS/OurPeople/DivisionsatMCYS/FamilyFormationStability/FamilyServicesDivision/TribunalfortheMaintenanceofParents.aspx

Ministry of Health, Singapore, n.d., Page on Healthcare Financing. http://www.moh.gov.sg/mohcorp/hcfinancing.aspx?id=310

Ministry of Manpower, Singapore, 2010, ‘Tripartite Guidelines on Re-employment of Older Employees Released’, 11 March, online edition. http://www.mom.gov.sg/Home/Press_Release/Pages/20100311-REOE.aspx

Mullan, Phil, 2002, The Imaginary Time Bomb: Why an Ageing Population is Not a Social Problem, New York: St Martin’s Press.

Mullan, Phil, 2004, ‘Ageing: The Future is Affordable’, spiked essays, 15 October, online edition. http://www.spiked-online.com/articles/0000000CA4E3.htm

Mullan, Phil, 2005, ‘Ageing and the “Pensions Crisis”’, spiked essays, 8 December, online edition. http://www.spiked-online.com/articles/0000000CAEB8.htm

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 1988a, Ageing Populations: The Social Policy Implications, Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 1988b, Reforming Public Pensions, Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 1988c, Health and Pension Policies under Economic and Demographic Constraints, Paris.

Ogawa, Naohiro, Amonthep Chawla, Rikiya Matsukura et al., 2009, ‘Health Expenditures and Ageing in Selected Asian Countries,’ Paper presented at the Expert Group Meeting on Population Ageing, Intergenerational Transfers and Social Protection, October 2009, in Chile.

Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, 2008, World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision, New York.

Singapore Government, 2009, Report on the State of the Elderly 2009, Singapore, online edition. http://app1.mcys.gov.sg/ResearchRoom/ResearchStatistics/ReportontheStateoftheElderlyR2009.aspx

Thang, Leng Leng and Kalyani K. Mehta, 2009, ‘The Dynamics of Multigenerational Care in Singapore’, Paper presented at a seminar on Family Support Networks and Population Ageing, 3–4 June 2009, in Qatar, online edition. http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:y1QYk5SlpIUJ:www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/groups/events_calendar/public/Doha/Leng%2520dynamics%2520of%2520Care%2520paperTHANG.doc+The+Dynamics+of+Multigenerational+Care+in+Singapore&cd=2&hl=en&ct=clnk

Tribunal for Maintenance of Parents, Family Services: Tribunal for Maintenance of Parents, 2005–2009. http://app1.mcys.gov.sg/ResearchRoom/ResearchStatistics/FamilyServicesTribunalMaintenanceofParent2005.aspx

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2009, ‘World Population Ageing 2009’, United Nations, online edition. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WPA2009/WPA2009_WorkingPaper.pdf

Westley, Sidney B., 1998, Asia’s Next Challenge: Caring For the Elderly, Asia Pacific Population and Policy No. 45, East-West Center (Program on Population), online edition. http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs/p&p045.pdf

Wijaya, Megawati, 2009, ‘Singapore Faces a “Silver Tsunami”’, Asia Times Online, 27 August, online edition. http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Southeast_Asia/KH27Ae01.html

World Health Organization (WHO), 2007, 10 Facts about Ageing and the Life Course, Geneva, online edition. http://www.who.int/about/contacthq/en/index.html

^ To the top

|