|

NTS Alert April 2010 (Issue 2)

INTEGRATING ADAPTATION INTO DEVELOPMENT POLICY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

Southeast Asia is potentially one of the more vulnerable regions to climate change impacts, as many of the countries in the region have relatively low levels of development, weak infrastructure, long coastlines, and a significant percentage of the population is still dependent on agriculture, a sector which is more climate-sensitive. Recognising this, developing countries in the region have been vociferous in their support for adaptation. This Alert looks at three countries – Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines – to examine the place of adaptation in government policy.

|

Introduction

Countries in Southeast Asia are already more susceptible to extreme weather events. Climate change increases their potential vulnerability to natural hazards; coastal geography means that these countries are more likely to be affected by sea-level rise, tropical storms and cyclones. Similarly, the agricultural sector in the region is also more likely to be affected on account of changes in the climate. Agriculture is the main source of livelihood in nearly all the countries in the region and the Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change (EACC) Report (World Bank, 2009) shows that changes in temperature will significantly affect crop yields and production, necessitating adaptation in the sector. While climate change could also potentially have implications for areas such as health, water supply and business, infrastructure and agriculture will prove to be key areas in the region that demand greater attention. The EACC Report suggests that the costs of adaptation could be US$75–100 billion a year, and East Asia and the Pacific are expected to face the highest costs with infrastructure accounting for the largest share. Growing population and the high concentration of human and economic activities in this mostly coastal region is also an important factor in adaptation needs and capacities.

As seen in the previous issue of this Alert, adaptation can either be planned or reactive. Often reactive adaptation takes place at an individual and local level, and is thus difficult to monitor or record. Planned adaptation, however, can be undertaken as part of an international agenda, regionally and, as is more common, by national governments. Increasingly, planned adaptation at a local level is also being undertaken by community-based and non-governmental organisations. Many international organisations and aid agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Oxfam, International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), and the United Nations are playing an increasing role in driving local adaptation programmes.

According to the Institute of Social and Environmental Transition’s (ISET) study of existing adaptation knowledge and measures in Southeast Asia, all policy and research approaches to adaptation in the region largely fall under the following categories: (1) national efforts to meet obligations of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); (2) assessment of climate change impacts and vulnerabilities, particularly around water and agriculture; (3) community-based adaptation strategies; (4) disaster management and disaster risk reduction and (5) economic analyses and adaptation research (ISET Report, 2008: 14).

In this Alert, we provide an overview of national policy plans and of measures that address key concern areas for most countries in terms of vulnerabilities. These are adaptation needs in agriculture such as changes in crop management, water use, the use of new types of seeds and disaster management, something which includes preparedness, building flood defences and efficient response systems.

^ To the top

Adaptation in Southeast Asia: National Policy Instruments

The National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a useful indication of a country’s strategy and policy on climate change. Ninety-one countries, including Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, have ratified the UNFCCC. As per Article 4.1b of the Framework, all member parties are to ‘formulate, implement, publish and regularly update national, and where appropriate, regional programmes containing measures to … facilitate adaptation to climate change’ (UNFCCC, 1994).

The initial national communications to the UNFCCC were submitted by Indonesia (1999), Thailand (2000), and the Philippines (2000). While presenting plans for mitigating Green House Gas (GHG) emissions, the communications have placed relatively less attention to adaptation, only acknowledging its importance but lacking a coherent and detailed policy on it.

Indonesia

Indonesia submitted its initial national communication to the UNFCCC in 1999. The document does not state a clear adaptation policy or a strategy for it. However, it recognises the importance of adaptation and technology in agriculture as well as other areas such as forestry, energy, and coastal resources. It states the need for a long-term adaptation strategy for the possibility of sea-level rise and the need for improving technology and innovation, and for information transfer in order to speed up adaptation. Its stated policy on adaptation in the 1999 document focused only on the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) (Indonesia’s National Communication to UNFCCC, 1999).

Indonesia’s National Action Plan (RAN-PI) for addressing climate change was formulated in 2007 with the aim of it serving as a guideline for various government institutions in carrying out coordinated and integrated efforts for tackling climate change, including adaptation. Along with the RAN-PI, it also formulated Indonesia’s Climate Change Adaptation Plan or ICCAP, which is based conceptually on the interaction between society, ecology and economy and ‘aims to embed a climate risk and opportunity management mechanism within national, provincial and local development plans’ (ISET Report 2008: 64) and is supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). In addition, Indonesia has proposed the Presidential Regulation, which will function as an umbrella to all activities related with climate change impact in terms of both mitigation and adaptation. As per the RAN-PI, adaptation to climate change is a key aspect of the national development agenda with its integration into the national development plans as the long-term objective. It also suggests that the adaptation agenda should be linked to the National Action Plan on Reduction of Disaster Risk (RAN-PRB). The RAN-PI as a policy instrument aims to integrate both adaptation and mitigation into various policy areas such as health, agriculture, disaster management, science and technology. It has a clear strategy for integrating the adaptation agenda in its development goals, which includes mainstreaming adaptation into the infrastructure planning and design – maintaining drains, building regulations for coastal development – as well as into other sectors’ policy such as agriculture, health and industry.

Thailand

Thailand has so far only submitted its first national communication to UNFCCC, which articulates its policy on climate change, both with regard to mitigation and adaptation. The communication includes information on vulnerabilities and adaptation, research and development, technology transfer and financial resources. It also expresses the need for greater institutional, technological and financial assistance in the areas of vulnerability assessment and adaptation planning. Further, Thailand has incorporated climate change issues into its social and economic development strategies. Thailand’s initial communication identifies adaptation options, although in more general terms, in the various sectors of concern, mainly agriculture and coastal management because of potential sea-level rises. The Thai government’s stated adaptation objective is ‘to enhance the research and development capacity’ in water resources conservation and agricultural practices. The key constraints in formulating an effective adaptation programme, according to the national communication, are the lack of sufficient research and development in climate and economic modelling as well as in specific areas such as new agricultural technology. There is particular emphasis on the need for technology improvement, research and development, and the need for the transfer of technology from developed countries to developing countries. This is mainly to facilitate vulnerability assessments and climate modelling in order to predict climate impacts.

In January 2008, the Council of Ministers passed a resolution acknowledging national strategies dealing with climate change management for 2008-2012, which includes the creation of adaptation ability to address and lessen vulnerability to climate impacts.

^ To the top

Philippines

The Philippines submitted its first national communication to the UNFCCC in December 1999. Its second communication is still in progress. For its national communication, the Philippines conducted detailed vulnerability assessments, especially in the agricultural sector. It includes detailed investigations into and options for adaptation in agriculture and the management of coastal resources, with a stress on the need for increased research in order to design and implement carefully planned adaptation strategies. A number of government bodies such as the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) Board, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and National Water Resources Board are involved in mapping an adaptation strategy. The communication recognises and addresses adaptation needs in much detail.

Other bodies have been created in order to deal with climate change and related areas. In 2007, the Presidential Task Force on Climate Change was created to conduct climate impact assessments, especially on the most vulnerable sectors such as water, agriculture and coastal areas. Another body, the Inter-Agency Committee on Climate Change was created in 1992 to serve as a national mechanism to coordinate all activities related to climate change. The Environment Management Bureau of the DENR has initiated the Climate Change Adaptation Phase 1, with the aim of developing sector-responsive adaptation activities (ISET, 2008: 62).

Governments in the region are aware of their adaptation needs, and while there are a number of impacts assessment studies and research underway, comprehensive national plans on adaptation are lacking. As Resurreccion et al. (2008) note in their ISET report, national plans on adaptation are still in the preparatory or planning stages in all countries in the region. These are being prepared by several different departments and sometimes inter-department government bodies although this coordination tends to be in a more ad hoc fashion. For a list of state and non-state initiatives related to climate change and adaptation, see Table 1 below.

Table 1: Climate Change Adaptation Initiatives in Southeast Asia

| Countries |

State/Non-State Policy and Action |

Indonesia |

UNFCCC: First National Communication with adaptation component

National Plan Addressing Climate Change (RAN-PI)

Draft National Strategy on Adaptation (ICCAP)

EcoSecurities: carbon trading

Nestle: water management

REDD: Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation |

Thailand |

UNFCCC: First National Communication National Strategy on Adaptation |

Philippines |

UNFCCC: First National Communication (section on adaptation)

Second National Communication draft in progress

IACCC: Climate Change Adaptation Project (WB-GEF and UNDP/MDG-F)

Three national bodies: IACCC, PTFCC and DENR Advisory Group on climate change

Philippine Network on Climate Change

Manila Observatory/klima: local adaptive management

SMART cell phone service provider for warning devices

Unilever: aquatic resources restoration

Provincial Government of Albay: mainstreaming CC-A

COPE (Christian Aid)

Oxfam |

Source: ‘Climate Adaptation in Asia: Knowledge Gaps and Research Issues in South East Asia’, ISNET Report, June 2008.

^ To the top

Agriculture

Agriculture is an important sector in the region. Despite rapid economic growth and structural transformation, a significant percentage of populations in most Southeast Asian countries are employed in agriculture. Most Southeast Asian poor live in rural areas and still rely on agriculture for their livelihoods. Poor subsistence farmers are also the most vulnerable to climate change. In many Southeast Asian countries, farmers have traditionally observed a number of practices to adapt to climate variability, for example intercropping, mixed cropping, agro-forestry, animal husbandry, and developed new seed varieties to cope with local climate shifts. Governments in the region are conducting vulnerability assessments in the sector and most of them are working closely with agricultural ministries.

Figure 1: Harvesting irrigated fields in Indonesia

Source: Curt Carnemark/ World Bank. Available at Flickr.com |

Many agriculture ministries frame adaptation as a way of improving agriculture or crop production systems. Indonesia has stated the need for research and technology to make agriculture more resilient and has suggested food diversification and the local dissemination of agricultural technology to farmers for locally-focused adaptation. In the framework of the RAN-PI, the Ministry of Agriculture in Indonesia has formulated a national strategy. The Agency of Agricultural Research and Development has identified and evaluated adaptive technologies, including the development of crop varieties that are high yielding, drought and inundation tolerant, as well as resistant to pests and diseases. The Agency has also identified and developed production technologies through appropriate crop, water and soil management, water conservation and its efficient utilisation, a cropping calendar for Java and a blue print for drought and flood anticipation (Las, 2007).

The agriculture sector in Thailand has adapted to developments in domestic and international economic and social environments. The Thai government’s adaptation plan includes a slow shift to organic agriculture. It has conducted impact studies to determine the effects of climate change on crop yields. The studies reflect a number of uncertainties, which present a number of constraints in applying an adaptation model. As an initial measure, the government has noted the usefulness of intensifying the conservation of drought resistant varieties; by improving crop varieties to drought tolerant types; by improving cropping practices to conserve water; and by promoting crop diversification. It also points out the need for an improvement in climate scenarios and achieving more suitable crop models.

Agriculture in Thailand also has adapted to local environmental conditions. According to Thailand’s initial national communication to UNFCCC, it has promoted soil conservation, reduction in the application of chemical pesticides and fertilisers, and even chemical-free or organic agriculture. Significantly, it admits that in the long-term it is difficult to study the effectiveness of adaptation measures adopted by individuals and communities locally.

Some precautionary measures suggested as adaptation options, while research and development are ongoing, include (National Communication to UNFCCC, 1999):

- Conservation and improvement of local drought resistant varieties

- Improvement of cropping practices to minimise water use

- Application of risk averse cropping systems

- Analysis of potential crop substitution in different regions

- Promotion of crop diversification programme

Agriculture is one of the major sectors for adaptation in the Philippines that has been identified by the government (the others include water and coastal resources). The country’s national communication stresses the need for support to farmers and an increase in the adoption of modern technology. The government has conducted vulnerability and adaptation studies in the agricultural sector and has identified a number of gaps that require attention. These include (National Communication of Philippines to UNFCCC, 2000):

- Vulnerability and assessment of production of other important crops (i.e. sugar cane, coconut, cash crops, etc.) and of livestock

- Assessment of the changes in geographical and seasonal distribution of thermal and water resources which are important to crop and livestock production

- Assessment of reduction in GHG emissions with the implementation of the Balanced Fertilisation Programme

- Assessment of reduction in GHG emission from different mixes of adaptation strategies

- Development of management methods from adaptation of agriculture systems to the predicted increased CO2 concentrations and associated climate change

- Assessment of impacts of intensive farming systems, especially because rice production needs to meet demands of increasing population

- Assessment of long-term effects of climate change on soil fertility and effectiveness of fertilisers and chemicals

^ To the top

Coastal and Disaster Risk Management

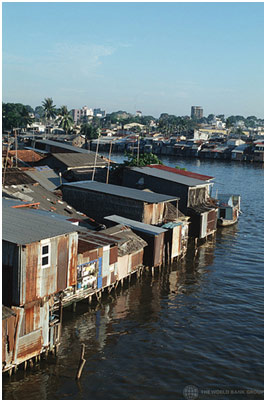

Coastal geography in the region means that many cities could potentially be affected by sea-level rise. Coastal infrastructure is an important component of adaptation in these countries and is recognised by governments as an important area because of the level of urbanisation and economic activities in some of the coastal cities.

Figure 2: Shanty town on the Saigon River, with downtown Saigon in background.

Source: Tran Thi Hoa/ World Bank. Available at Flickr.com |

The Philippines ranks high among the most disaster-prone countries and is exposed to several powerful tropical cyclones or storms annually. In 2009 for instance, the tropical storms Ketsana and Parma caused hundreds of casualties and severe damage to housing and other property. In response to concerns about increasing disaster risks arising from climate change, the Philippines Government enacted a new legislation, called the Climate Change Act of 2009, which will integrate disaster risk reduction measures into climate change adaptation plans, development and poverty reduction programmes (ISDR, 2009). The Act also aims to invite foreign funding for adaptation and disaster risk reduction (Romero, 2009). The primary function of the commission is to ‘ensure the mainstreaming of climate change, in synergy with disaster risk reduction, into national, sectoral and local development plans and programmes’ (Preventionweb, 2009).

In a joint project by the NEDA and UNDP and the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), another project, which recognises the importance of adaptation and disaster risk reduction, was unveiled in 2009. The project ‘Integrating Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation (DRR/CCA) in Local Development Planning and Decision-making Processes’ aims to mainstream the related concerns of disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation into local decision-making and planning processes.

According to Smith Dharmasaroja, chair of the Thai Government’s National Disaster Warning Administration, Bangkok’s land subsidence coupled with rising sea-levels put the city at the risk. To counter this threat, disaster prevention experts are now advocating the construction of a 100 billion baht (US$3 billion) flood prevention wall to protect Bangkok (Kisner, 2008). Thailand has conducted a number of vulnerability assessments identifying impacts on inundation of coastal areas and existing drainage and flood control facilities. However, in its national communication it expresses the inadequacy of these when it comes to drawing conclusions or formulating policy recommendations with regard to adaptation options. The Communication states the need for more research, while suggesting some options for adapting to sea-level rise (Thailand’s First National Communication to UNFCCC):

- Establishing a coastal hazard management subcommittee to develop policies, strategies and guidelines for coastal hazard management

- Providing guidelines on management and development of coastal areas

- Improving drainage and flood control facilities

- Improving cropping systems suitable to such environmental change, using organic matter to improve salty soil conditions

- Improving crop cultural practices

^ To the top

Local Adaptive Strategies

A number of non-government actors are facilitating adaptation measures in the region, especially in rural areas. Most community-based adaptation projects are being run by international organisations, NGOs and civil society. There are a few projects where the government is aided by international donor bodies and development organisations to work jointly with local bodies and civil society organisations.

The UNFCCC documents local adaptive strategies in its database, which intends to facilitate the transfer of coping strategies, practices and local knowledge. Some examples of local autonomous coping strategies include integrated community-based risk reduction in Indonesia, which is a Red Cross project aimed to develop capacities and ‘to learn about integrating risk reduction, climate change adaptation, and micro-finance in one holistic project’ (UNFCCC adaptation database). This includes community organisation and mobilisation, formation and training of volunteer groups, self-help groups and availability of micro-credit to complement these activities among others.

In Thailand, in the Lower Songkram River Basin, indigenous forecasting methods – ants removing their eggs from the nest is seen as a sign of rain while a decrease in mushrooms can signal drought – is seen as a community-based case of autonomous adaptation. Other coping mechanisms in the agricultural sector include the ability to grow two different types of rice for dry and wet seasons, respectively, and the diversification of livelihoods. In the Philippines, according to the UNFCCC coping strategies database, indigenous communities of the Philippines use drums and horns to alert their communities against storms and cyclones. Local elderly people in the community, based on abnormal behaviour of animals and the appearance of particular clouds, forecast and predict cyclones and storms.

Other examples of community-based adaptation, where international actors and non-government organisations and players are involved, include crop selection, alternative cultivation methods, soil conservation, dissemination of knowledge and information, capacity building and improved low-cost housing designs that are more flood resistant.

^ To the top

Integrating Adaptation into Development Policy

An overview of government adaptation policies in some countries in the region show that these are largely still in the planning stages, and while governments have conducted some vulnerability assessments and identified risk areas and some adaptation options, concrete strategies and ground-based measures are still absent from national policies. The primary reasons cited for this in national communications are the lack of adequate research support, technology and resources. There is also a considerable uncertainty expressed in the risk assessments, making it difficult to plan ahead.

On the other hand, many local community-based strategies are being encouraged and recognised by international organisations and NGOs. These concentrate largely on agriculture and natural disaster amelioration. According to Herminia Francisco (2008) measures that entail big investments, like infrastructure for flood protection and retreat strategies, warrant a central role for the national governments. Further, local governments and civil society can work together in areas such as disaster management, early warning systems and capacity building.

A common approach to adaptation, however, is that of continued and sustained development, be it at a national or a local level. At a national level, governments recognise the need for incorporating adaptation goals into national development agendas. Using this approach, different government ministries are working in tandem in terms of adaptation. However, the means to put concrete adaptation measures in place is a still a challenge for most governments on account of the lack of financial resources and access to technology, as well as competing development goals (Francisco, 2008).

^ To the top

Conclusion

It is too early to assess the effectiveness of adaptation programmes and instruments in the region, as these are still in a preparatory stage with limited research capacity and many programmes are yet to be implemented. However, in terms of the needs of specific sectors, the local governments often respond to areas that fall within their normal developmental mandate without approaching it specifically as adaptation. This is especially the case for disaster preparedness. In the absence of adequate research and accurate climate risk assessments, it would serve governments well to continue their development strategies taking into consideration adaptation needs.

Reference

‘Adapting to Climate Variability and Change – A Guidance Manual for Development Planning’, USAID, August 2007.

‘Adaptation to Climate Change by Reducing Disaster Risks: Country Practices and Lessons’, International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) Briefing Note 2, United Nations, November 2009. Available at http://www.preventionweb.net/files/11775_UNISDRBriefingAdaptationtoClimateCh.pdf

‘Climate Change: Impacts, Vulnerabilities and Adaptation in Developing Countries’, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2007.

‘Climate Adaptation in Asia: Knowledge Gaps and Research issues in South East Asia’, Report of the South East Asia Team, ISET-International and ISET-Nepal, 2008. Available at http://www.preventionweb.net/english/professional/publications/v.php?id=8126

Francisco, H., ‘Adaptation to Climate Change: Needs and Opportunities in Southeast Asia’ in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp 7–19, April 2008.

Indonesia’s Initial National Communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 1999.

‘Indonesia and Climate Change: Current Status and Policies’, PEACE, Indonesia, 2007.

Kisner, Corrine, ‘Climate Change in Thailand: Impacts and Adaptation strategies’, Climate Change case study, Climate Institute, July 2008. Available at http://www.climate.org/topics/international-action/thailand.htm

Las, Isral, ‘Indonesia boosts R&D to cope with climate change’, The Jakarta Post, 6 December 2007.

Philippines’ First National Communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2000.

Romero, Paulo, ‘GMA signs Climate Change Act’, The Philippine Star, 24 October 2009. Available at http://www.philstar.com/article.aspx?articleid=517009&publicationsubcategoryid=63

Thailand’s Initial National Communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Office of Environmental Policy and Planning, Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment. Bangkok, Thailand, 2000.

‘The Economics of Climate Change in Southeast Asia: A Regional Review’, Asian Development Bank Report, April 2009.

The National Action Plan for addressing Climate Change, Indonesia, 2008.

^ To the top |