|

Transitional justice in South and Southeast Asia: Integrating judicial and non-judicial measures

Transitional justice redresses legacies of past gross violations of human rights, through mechanisms such as prosecutions, truth-finding, reparation and institutional reforms. As each mechanism has its limitations, transitional justice processes that integrate different measures and constructively engage with stakeholders would be more effective in healing the wounds from past wrongdoings. Three factors are seen to be key: the capacity and political will of the government concerned, participation of local communities and civil society, and international involvement.

By Lina Gong

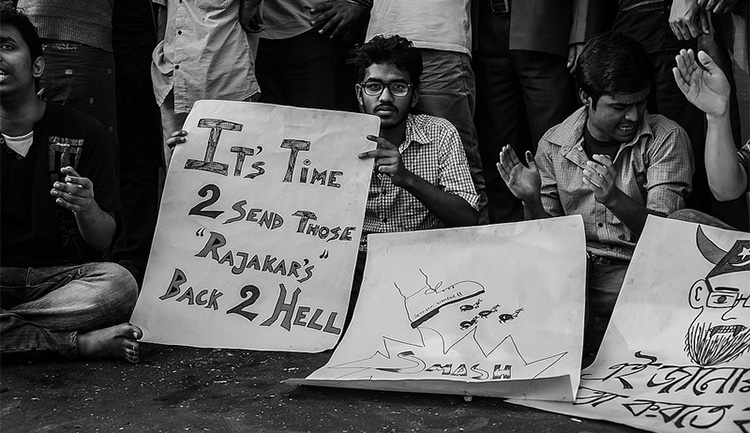

| The protests in Bangladesh in February 2013 after the sentencing of two men convicted of war crimes during the independence war of 1971 raised questions about how to effectively implement transitional justice measures in a country.

Credit: M. Hasan / flickr. |

|

Contents:

Recommended citation: Lina Gong, ‘Transitional justice in South and Southeast Asia: Integrating judicial and non-judicial measures’, NTS Insight, no. IN13-04 (Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, 2013).

| |

Introduction

Asia has witnessed numerous civil conflicts in the past few decades, many of which have been brutal. In the aftermath of these conflicts, international organisations, civil society and victims have called for transitional justice, arguing that this is a crucial step to social reconciliation and durable peace. In March 2013, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution encouraging accountability for the Sri Lankan civil war and reconciliation in the country;1 and in April, Amnesty International issued a report urging meaningful progress on justice for victims of the Aceh conflict.2

However, transitional justice processes have at times themselves fomented controversy. In early 2013, the International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh sentenced two men for their role in gross violations of human rights during the independence war of 1971. Violent protests followed, resulting in over a hundred deaths.3 Such incidents highlight the need to examine transitional justice, its mechanisms and their implementation more critically.

To that end, this NTS Insight begins by reviewing major discussions on transitional justice, accountability and reconciliation. It then looks at the workings of transitional justice in Aceh (Indonesia), Bangladesh, Cambodia and Timor-Leste, exploring the similarities and differences in the issues and challenges faced by these regions/countries. Based on the analysis, this NTS Insight identifies several factors that are key to effective transitional justice for countries in Asia and beyond, and argues for an integrated approach to transitional justice.

^ To the top

Transitional justice: Concept and implementation

The Nuremberg Trials in the 1940s were the world’s first experience of transitional justice.4 Today, transitional justice is understood to refer to the full range of mechanisms and processes for redress of past systematic violations of human rights.5 It spans judicial as well as non-judicial measures. The pursuit of transitional justice starts after the abuses have been brought to an end, but the specific timing is subject to the local context.

The goals of transitional justice are to, first, reconcile societies divided as a result of grave human rights violations; second, end impunity and establish the rule of law; and third, prevent recurrence of abuse and repression through ensuring accountability, acknowledging culpability and establishing shared accounts of past abuses. Transitional justice is therefore a broad concept that encompasses retributive justice, restorative justice, reparative justice and social justice (see Table 16). It is operationalised through various mechanisms: prosecution, truth-finding, reparation, institutional reform, education and commemoration.

|

Table 1: Components of transitional justice.

|

Components |

Aims and functions |

Examples of mechanisms and measures |

Retributive justice |

- End impunity and seek accountability for serious abuses through judicial measures.

- Contribute to enhancing rule of law.

|

- International: International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda; International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

- Hybrid: Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia.

- Domestic: International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh.

|

Restorative justice |

- Establish the truth about the past.

- Reconcile social divisions through collective memory.

|

- Truth commissions: Timor-Leste Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR); Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa.

- Commemoration: Establishment of a memorial at the Choeung Ek killing fields in Cambodia.

- Reintegration of perpetrators into their communities in Timor-Leste.

|

Reparative justice |

- Provide reparation for suffering and losses, in both symbolic and financial forms.

|

- A valorisation programme in Timor-Leste that provides recognition and financial compensation to veterans (this programme also has some elements of restorative justice).

- A development assistance programme by the Aceh Reintegration Agency in cooperation with the World Bank (this programme also addresses social justice concerns as it provides access to economic development).

|

Social justice |

- Address the root causes and enabling factors of the systematic abuses that had taken place. This could include looking at political, social and economic injustice.

|

- Revisions of discriminatory laws.

- Incorporation of gender into transitional justice.

|

Sources: Based on Kora Andrieu, ‘Transitional justice: A new discipline in human rights’, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, 18 January 2010, http://www.massviolence.org/Article?id_article=359; Alexander L. Boraine, ‘Transitional justice: A holistic interpretation’, Journal of International Affairs 60, no. 1 (2006): 17–27; Albert W. Dzur, ‘Restorative justice and civic accountability for punishment’, Polity 36, no. 1 (2003): 3–22, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3235421; Simon Robins, ‘Challenging the therapeutic ethic: Victim-centred evaluation of transitional justice process in Timor-Leste’, The International Journal of Transitional Justice 6 (2012): 83–105, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijr034; Roman David and Susanne Y.P. Choi, ‘Victims on transitional justice: Lessons from the reparation of human rights abuses in the Czech Republic’, Human Rights Quarterly 27, no. 2 (2005): 392–435, http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2005.0016

|

^ To the top

Limitations of individual mechanisms

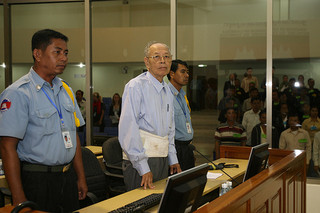

Despite the existence of a variety of mechanisms, transitional justice is often thought of solely in terms of the prosecution and punishment of perpetrators. However, judicial processes have several inherent limitations. Mass atrocities are usually carried out by a group of people (who share the same ethnic, racial, religious or political identity). Yet, in most cases, only the top leaders and those most responsible are prosecuted.7 Such selective prosecutions could convey the message that only a few individuals are guilty.8 Another limitation was exposed by the death of Ieng Sary, a defendant in the Khmer Rouge trials, in March 2013. The slowness of the judicial process means that many suspected perpetrators may not live long enough to see through their trials. Another issue is the assumption that war crimes trials are vital for achieving reconciliation; some have argued that there is insufficient empirical data to support that conclusion.9

Ieng Sary, one of the leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime, passed away on 14 March 2013, before the end of his trial – thus highlighting one of the problems with relying solely on the judicial mechanism to meet the goals of transitional justice.

Credit: Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia / flickr. Non-judicial mechanisms also present challenges. While truth and reconciliation commissions are supposed to establish a comprehensive account of the past, the different parties – victims, witnesses and perpetrators – often interpret their experience differently. Thus, it is very difficult to establish a complete version of truth acceptable to the whole society. Moreover, the recollection of past abuses could re-traumatise victims, survivors and their families.10 In the case of material reparation to victims, it is no easy task to measure suffering and loss.

Importance of an integrated approach

Given that each mechanism has specific functions and limitations, it is crucial to approach transitional justice in a holistic manner, balancing judicial with non-judicial measures. Accountability through judicial mechanisms ends impunity and to some degree deters future occurrence of systematic abuse. The punishment of perpetrators gives a sense of emotional relief and closure to victims and their families, and also serves as a symbol of the transition to the rule of law.

Non-judicial measures are important complements to trials, as they fill the gap left by selective prosecutions. Truth and reconciliation commissions provide a platform for victims and their families to make their suffering and grief heard. Acknowledgements of culpability and expressions of contrition (from perpetrators of past abuse) could help heal wounds, and rebuild relationships between communities and individuals divided by having stood on different sides of a conflict. The truth-finding process also reveals the patterns and enabling factors behind the past abuse, and thus contributes to prevention. Reparations in the form of development assistance and capacity building help victims address the challenges of daily life. The experience of different areas and countries with transitional justice processes bears out the importance of an approach that integrates a range of mechanisms (rather than relying solely on judicial measures) – as shall be evident from the discussion in the next section.

^ To the top

Pursuit of accountability and reconciliation in Asia

Aceh, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Timor-Leste have experienced massive abuse of human rights during their respective intra-state conflict or independence war, and each has begun the process of confronting past atrocity crimes. It would thus be useful to review the mechanism(s) chosen in each case, and how effective they have been at meeting the goal of reconciling divisions in post-conflict situations.

Aceh (Indonesia)

Aceh experienced conflict for nearly two decades starting from the 1980s, as the Indonesian military launched military offensives against separatists in the area. The fighting had a devastating impact on the local population. Thirty-three thousand civilians were killed,11 and widespread human rights abuses were reported, including torture, rape, enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention and indiscriminate attacks.12 Women were subject to systematic sexual violence.

A peace deal was finally struck between the Indonesian government and the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, or GAM) in 2005. The memorandum of understanding included several transitional justice measures: the establishment of a Human Rights Court and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission; economic assistance to victims; and institutional reforms to strengthen the rule of law. However, eight years on, the Human Rights Court and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission have yet to be established.

The lack of progress could be attributed in part to a dearth of interest, on the part of the national government as well as GAM representatives. Transitional justice was not prioritised in the negotiations, except for amnesty issues.13 The agreement grants amnesty to GAM fighters but not government security forces, which explains the lack of political will from the government. There have even been private discussions on the government side about abandoning the plans for the Human Rights Court and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. GAM too had concerns about their people being brought to trial despite the amnesty. The mediator thus encouraged GAM negotiators to focus more on the future.14

There are also few avenues for transitional justice at the national level in Indonesia. The country’s human rights court only has jurisdiction to investigate crimes committed after 2000. Furthermore, its mandate covers only genocide and crimes against humanity, while abuses committed in Aceh also included torture, extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearance.15

In addition, there are no provisions for truth-finding at the national level, and there is reluctance to pursue such measures. Indeed, parliamentary and military officials have emphasised the importance of looking forward.16 Even local authorities have not been very enthusiastic. A member of the provincial parliament of Aceh stated that a local truth and reconciliation commission would be considered only after the passing of a national law to establish a truth and reconciliation commission for human rights violations committed between 1966 and 1998, when Indonesia was under an authoritarian regime.17

There has however been some progress in reparation. The government established the Aceh Reintegration Agency (Badan Reintegrasi Aceh, or BRA) to help affected civilians recover from conflict-inflicted damage.18 The Agency, in cooperation with the World Bank, has implemented an assistance programme to facilitate local development and improve local people’s lives. By 2007, USD26.5 million had been invested and 1,724 villages had benefited from the project. The Agency also provided monetary reparation to the heirs of persons who were killed or went missing in the conflict in accordance with traditional Islamic compensation. 19

Bangladesh

During the Bangladesh independence war of 1971, over a million people were killed and between 200,000 and 400,000 women and girls raped – allegedly by the Pakistani army and its collaborator, Jamaat-e-Islami. This has been the subject of calls for justice from many Bangladeshis; and the International Crimes Tribunal was established in 2010 in response. Its three judges and ten prosecutors are all Bangladeshi nationals. The Tribunal has thus far indicted eleven people, nine from the Jamaat-e-Islami and two from the Bangladesh Nationalist Party. By May 2013, four people had been convicted of crimes ranging from genocide and rape to abduction and torture. Three of them had been sentenced to death and the fourth given life imprisonment. 20

However, the trials have been marred by allegations of irregularities in the proceedings and improper political manoeuvrings. The government’s move to amend the country’s war crimes law to empower the tribunal to bring to trial any organisation that committed crimes during the war cast doubt on the independence of the judiciary.21 External legal experts also questioned the speed of the investigation: does the court have the capacity to investigate cases forty years old within a span of less than three years? Also, a witness for the defence reportedly went missing before he could testify.22 Such (perceived) shortcomings in the judicial process fuelled dissatisfaction, particularly among supporters of those accused of perpetrating war crimes. When two Jamaat-e-Islami leaders were sentenced in February 2013, their supporters questioned the credibility of the court and its decisions, and clashes were seen between supporters of the convicted leaders and security forces. The events in Bangladesh suggest that there is a need for judicial processes to be carefully managed, and also accompanied by other measures such as truth-finding. Otherwise, instead of effecting reconciliation, transitional justice may, as in Bangladesh, just deepen societal schisms.

Lack of engagement with key stakeholders has been another source of discontent. Civil society groups played a role in pressing the government to initiate the trials after the Awami League won the election in 2008.23 However, while the UN Development Programme (UNDP) provided some advice on the formation of the tribunal, engagement with civil society and international actors has in general been very limited. This has led to criticisms of injustice and lack of transparency. Victims had hoped that their voices could be heard and their sufferings recognised24 – but little has been done on this front.

^ To the top

Cambodia

During the rule of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia between 1975 and 1978, up to 1.7 million Cambodians died of extrajudicial execution, overwork, starvation and disease.25 After the Khmer Rouge regime was overthrown, the Cambodian government brought some Khmer Rouge leaders to trial. However, those trials, held in 1979, have been widely rejected as illegitimate because they breached certain international justice standards, such as trying the accused in absentia and acting on the presumption of guilt.26 In 2005, a UN-backed tribunal, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), was established. The ECCC has so far tried five people considered most responsible for the grave violations of human rights during the Khmer Rouge era.27

ECCC processes demonstrate two characteristics: victim participation and vibrant civil society engagement. Victims can participate as civil parties in the ECCC trials, with the right to engage their own legal representatives to question the defendants and request reparation. The people thus have a channel to seek answers to their questions concerning the abuses. For instance, the testimony of the defendants in Cases 001 and 002 may answer questions lingering in the minds of victims, such as why their relatives were killed. Importantly, victims also have the opportunity to have their grievances heard. In the on-going Case 002, victims testified against Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, top leaders of the Khmer Rouge, in early June 2013.28

The involvement of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) is another notable feature of Cambodia’s transitional justice processes. NGOs lobbied for justice for victims and survivors and reconciliation of a fragmented society. The Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee submitted a petition signed by 84,195 Cambodians to the UN in 1999, requesting the establishment of an international tribunal.29 After the agreement on the ECCC was reached in 2003, NGOs initiated a wide range of activities to complement tribunal processes, including public outreach, legal advisory services and psychological consultations. They have also made efforts to provide reports on the trials.30

Cambodia’s transitional justice processes have also included commemoration and education. A research committee was established in 1982 to document information related to the atrocities committed during the Khmer Rouge era. Choeung Ek, the site of former killing fields, is now a memorial, and the Cambodian government encourages visits to the area. In 1984, the government set 20 May as the ‘National Day of Anger’ to condemn the abuses and remind people of the importance of preventing the recurrence of such atrocities.31 A textbook on the history of the Khmer Rouge era was jointly published in 2007 by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport and the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), an NGO that has documented Khmer Rouge history since 1995.

Although Cambodia has placed emphasis on judicial and non-judicial measures, the transitional justice processes in the country still face questions and challenges. There have been repeated accusations of political interference since the beginning of the negotiations between Cambodia and the UN on the ECCC.32 For instance, the government yielded to the refusal of high-ranking officials to give testimony during the investigation of Case 002 even though under its agreement with the UN, the government has the obligation to compel these officials to cooperate. It is also accused of interfering with the investigation of Cases 003 and 004.33

Reparation is another issue that remains to be settled. Survivors and families of victims consider reparation – in the form of education, healthcare and other material assistance – to be critical to peace and reconciliation;34 and 4,000 victims presented a wish list of reparations to the ECCC in 2011. However, according to ECCC internal rules, survivors and families of victims would only receive collective and symbolic reparation from the ECCC trials; and the interpretation of ‘collective and symbolic’ remains open.

Timor-Leste

Between 1975 and 1999, there were grave violations of human rights by Indonesian troops and Timorese militia in Timor-Leste (also known as East Timor).35 After independence, measures to confront past atrocity crimes were implemented by the UN, Indonesia and Timor-Leste. The UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) set up Special Panels for Serious Crimes within the country’s domestic courts to exercise justice over genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, torture, murder and sexual offenses committed between 1 January and 25 October 1999 (the period immediately before and after the referendum for independence during which brutal violence and abuses against civilians occurred). Each panel consisted of one local judge and two international judges. By the end of 2003, 38 convictions had been handed down. Those convicted were locals, and most were low-ranking military officers. When the UNTAET completed its mandate in 2002, the responsibility for serious crimes was transferred back to Timor-Leste. 36

On Indonesia’s part, it established an Ad Hoc Human Rights Court for East Timor. However, the court has come under strong criticism.37 It tried eighteen persons, mainly Indonesian officers; but there were only two convictions, and both were East Timorese. Furthermore, few victims were produced as witnesses during the trials.

Within Timor-Leste, non-judicial measures are clearly favoured by the government. ‘Forgiveness and forgetting’ have been the keywords in government-led campaigns of reconciliation.38 Jose Ramos-Horta, former President and Prime Minister of Timor-Leste, pointed out on several occasions that restorative justice was more important and desirable for the country. 39 Xanana Gusmao, another former President, believes that rigorous prosecution may risk human rights and peace.40

Several steps have been taken to promote reconciliation. President Gusmao visited anti-independence Timorese who had sought refuge in West Timor out of fear of revenge by their countrymen.41 The Timor-Leste Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR) was set up in 2001 to investigate violations of human rights between 1974 and 1999 and facilitate reconciliation. The commission issued its report in 2005.42

Victims in Timor-Leste also tend to favour non-judicial measures. They rank economic support and reparation higher than other measures of transitional justice. They also want to be recognised for their contributions to independence.43 To address this, the government introduced a series of policies aimed at helping veterans. Significantly, it is not just members of the resistance movement that are recognised as veterans; those who served in the Indonesian government and armed forces can claim veterans’ benefits as well.44 Such policies have helped reduce tensions and confrontations between groups that had been on opposing sides of the struggle for independence.

Civil society has also played instrumental roles. NGOs and the Catholic Church have undertaken victim support programmes and memorial activities.45 In addition, local NGOs and community leaders have held ceremonies to receive refugees from West Timor, and they have encouraged some of them to publicly acknowledge their role in the human rights abuses that were committed – so as to facilitate their reintegration into the community.

Although the government and the public share the view that reconciliation is more important than prosecution at this stage, this does not mean the complete rejection of judicial measures. In 2008, families of the victims of past abuses presented a petition to the national parliament demanding that the perpetrators be brought to justice. At the same time, however, the petition also included demands for reparation.46

^ To the top

Challenges and lessons

Each country discussed above took a different approach to transitional justice, and achieved differing levels of success in achieving the goal of reconciliation. Cambodia has seen a relatively balanced integration of different measures and meaningful participation of relevant actors. Aceh and Timor-Leste have also employed a mix of judicial and non-judicial measures. However, the judicial processes in Aceh and Timor-Leste have thus far led only to the prosecution of low-ranking soldiers and militants; and non-judicial measures have been more emphasised. In Bangladesh, the focus has been on the judicial mechanism. Three issues play an important role in determining the effectiveness of each country’s approach to transitional justice: (1) the political will and capacity of the government concerned; (2) engagement with the people and civil society; and (3) international dynamics.

Political will and capacity

Political will is vital as the responsibility to seek accountability and reconciliation rests primarily with the government. However, governments can be reluctant to pursue transitional justice, particularly where there are links between a government and perpetrators. In Cambodia for instance, Prime Minister Hun Sen has rejected the call for more prosecutions. As some officials in the current government are former Khmer Rouge soldiers (including Prime Minister Hun Sen), this is perhaps not a surprising decision. In Indonesia, the country’s security forces had been involved in fighting the separatist movement in Aceh on behalf of the central authorities, which explains the lack of will to vigorously pursue judicial measures.

Infrastructure and intellectual capacity are also often destroyed during periods of conflict and mass violence. For example, during the Khmer Rouge era, intellectuals were specifically targeted. Such loss of capacity reduces the ability of countries to pursue transitional justice. In Timor-Leste, the adult literacy rate was only 38 per cent in 2001.47 Without a pool of intellectuals and professionals, it has been unable to independently conduct trials that conform to international standards.

Financial capacity is another constraint. The Special Panels for Serious Crimes in Timor-Leste stopped operations partly because of funding issues. In Cambodia, the cost of the ECCC is covered by the UN and international donors, with the Cambodian side providing venues, facilities and personnel. The Cambodian government cannot afford to finance the tribunal by itself.

Participation of victims and civil society

Transitional justice has evolved from being perpetrator-focused to being victim-oriented out of increasing recognition that mechanisms that respond to people’s claims and needs are more effective at achieving reconciliation. Victims in Cambodia, Timor-Leste as well as Bangladesh have identified reparation, recognition of their suffering and grievances, and confessions by perpetrators as their primary demands.48

Hearing perpetrators acknowledge what happened could help facilitate reconciliation in a society. For instance, the amount of animosity towards Duch, a former Khmer Rouge leader who had admitted his crimes during his trial and asked for forgiveness, is slightly lower than that felt towards other defendants who continued to deny their involvement in the genocide.49 The ECCC’s outreach programme supports this process of acknowledgement and healing by encouraging the public and victims to engage with the trial proceedings. In Bangladesh, victims also value the recognition of their suffering, but lack the necessary range of platforms to share their experience. Their only channel is the trials, which to some extent explains the demands for a harsher sentence for Abdul Quader Mollah, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment by the country’s International Crimes Tribunal.

Provision of basic needs and elimination of poverty are also critical for peace and reconciliation,50 as mass violence inflicts physical and mental strains as well as financial losses. Processes that take this into account would win support more easily. For instance, the Aceh Reintegration Agency (BRA)-World Bank programme has closely engaged with local communities with regard to the selection of projects.

NGOs are also important, as they can facilitate communications between key stakeholders. They are often familiar with challenges on the ground, have expertise on policies and procedures, and have developed close relationships with local communities. As such, they are well-placed to provide critical support services. For instance, NGOs in Cambodia have successfully encouraged many victims to come forward as witnesses and civil parties in the ECCC trials. They have also helped victims submit applications and educated them about their rights.51 In addition, NGOs specialising in legal and judicial issues help ensure that trial standards are met. In Aceh and Timor-Leste, NGOs and local community groups have served as bridges between victims, the government and international actors.

International and regional involvement

The involvement of the international community is also important, particularly in providing financial and technical assistance. The ECCC trials in Cambodia relied heavily on international inputs. Rebuilding efforts in Aceh and Timor-Leste have also benefited tremendously from the efforts of international actors.

Countries emerging from mass violence often lack the capacity to pursue transitional justice. International actors fill this gap by providing financial assistance, expertise and training. For example, between 2006 and 2009, the European Union provided over USD5 million to fund a project in Aceh. This initiative saw the UNDP collaborating with Indonesia’s National Development Planning Agency (Badan Perencanaan dan Pembangunan Nasional, or BAPPENAS) and its Decentralisation Support Facility to enhance people’s access to justice and strengthen the institutional capacities of justice systems.52 Another example is the UN Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT), which assisted with judicial reform and provided training for the country’s police force.53

Geopolitics is a delicate factor behind the choice of approach to transitional justice. The reluctance of the leadership in Timor-Leste to push for judicial processes is partly due to concern over its relationship with Indonesia. The Indonesia factor also partly explains lack of international interest in establishing an international tribunal in Timor-Leste. In the case of Bangladesh, the country had requested technical assistance and expertise from UN agencies before setting up its International Crimes Tribunal in 2009 and the UN had initially agreed to help.54 However, Pakistan, due to its role in the 1971 mass atrocities, strongly opposed UN involvement in the trials and lobbied to prevent that from happening.55 Eventually, the UN pulled back from providing formal help through the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (which deals with issues related to human rights abuses) and instead offered limited assistance through the UNDP.

^ To the top

For countries emerging form civil war such as Sri Lanka, transitional justice could help heal divisions. While judicial processes are the most obvious measure, such countries would do well to pursue approaches that combine various mechanisms.

Credit: Church Mission Society / flickr.

Conclusion

The cases discussed here demonstrate that judicial measures are not by themselves necessarily sufficient for ensuring peace and reconciliation. Even the victims themselves sometimes prefer non-judicial measures. The cases thus underline the need to address the range of physical, mental and financial issues faced by individuals and communities exposed to mass violence. A holistic approach incorporating a variety of mechanisms and measures must thus be considered and implemented, as had happened in Cambodia. The types of measures used must also take into account local contexts and needs. Hence, it is of vital importance that transitional justice processes engage with all relevant stakeholders – victims, perpetrators, the state, local stakeholders, international actors and NGOs.

The experiences of Aceh, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Timor-Leste provide lessons for other countries in the region just emerging from past repression and systematic abuse of human rights such as Myanmar and Sri Lanka. In Myanmar, sectarian clashes between Muslims and Buddhists have raised concerns that the violence may upset the country’s progress. In Sri Lanka, which is recovering from civil war, growing waves of anti-Muslim activities have been seen. Effective transitional justice could end impunity and help advance social reconciliation in those countries, thus preventing tensions from escalating and reducing the likelihood of the recurrence of human rights abuses.

^ To the top

Notes

-

UN General Assembly, ‘Promoting reconciliation and accountability in Sri Lanka’ (A/HRC/22/L.1/Rev.1, New York: UN, 19 March 2013).

-

Amnesty International, Time to face the past: Justice for past abuses in Indonesia’s Aceh province (New York, NY: Amnesty International, 2013), 32 and 53, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/ASA21/001/2013/en

-

Jim Yardley, ‘Politics in Bangladesh jolted by daily demonstrations’, The New York Times, 12 February 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/13/world/asia/politics-in-bangladesh-jolted-by-huge-protests.html?_r=3&. See also: Lina Gong, ‘Justice for war crimes: Retribution, or reconciliation?’, NTS Bulletin, March (Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies (NTS), 2013), http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/rsis/nts/html-newsletter/bulletin/nts-bulletin-mar-1301.html

-

Kora Andrieu, ‘Transitional justice: A new discipline in human rights’, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, 18 January 2010, http://www.massviolence.org/Article?id_article=359

-

UN, ‘Guidance note of the Secretary-General: United Nations approach to transitional justice’ (New York: UN, March 2010), http://www.unrol.org/files/TJ_Guidance_Note_March_2010FINAL.pdf

-

There are different ways of categorising the components of transitional justice, and the boundaries between different kinds of justice are blurred. See: Andrieu, ‘Transitional justice: A new discipline in human rights’; Alexander L. Boraine, ‘Transitional justice: A holistic interpretation’, Journal of International Affairs 60, no. 1 (2006): 17–27; Albert W. Dzur, ‘Restorative justice and civic accountability for punishment’, Polity 36, no. 1 (2003): 3–22, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3235421; Simon Robins, ‘Challenging the therapeutic ethic: Victim-centred evaluation of transitional justice process in Timor-Leste’, The International Journal of Transitional Justice 6, no. 1 (2012): 83–105, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijr034; Roman David and Susanne Y.P. Choi, ‘Victims on transitional justice: Lessons from the reparation of human rights abuses in the Czech Republic’, Human Rights Quarterly 27, no. 2 (2005): 392–435, http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2005.0016

-

The low number of prosecutions is linked to the complexity of the atrocity crimes, the large number of people involved, and the slow and long proceedings.

-

Andrieu, ‘Transitional justice: A new discipline in human rights’.

-

Laurel E. Fletcher and Harvey M. Weinstein, ‘Violence and social repair: Rethinking the contribution of justice to reconciliation’, Human Rights Quarterly 24, no. 3 (2002): 573–639, http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2002.0033

-

Andrieu, ‘Transitional justice: A new discipline in human rights’.

-

Edward Aspinall, Peace without justice? The Helsinki peace process in Aceh (Report, Geneva: Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2008), http://www.hdcentre.org/uploads/tx_news/56JusticeAcehfinalrevJUNE08.pdf

-

Ross Clarke, Galuh Wandita and Samsidar, ‘Executive summary’, in Considering victims: The Aceh peace process from a transitional justice perspective (Jakarta: International Center for Transitional Justice – Indonesia, 2008), http://ictj.org/publication/considering-victims-aceh-peace-process-transitional-justice-perspective

-

Scott Cunliffe et al., Negotiating peace in Indonesia: Prospects for building peace and upholding justice in Maluku and Aceh (IFP Mediation Cluster, Country Case Study: Indonesia, New York, NY: International Center for Transitional Justice, 2009), http://ictj.org/publication/negotiating-peace-indonesia-prospects-building-peace-and-upholding-justice-maluku-and

-

Ibid., 15.

-

Amnesty International, Time to face the past, 32 and 53.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Nani Afrida, ‘Jakarta’s homework and maintaining trust in Aceh’, The Jakarta Post, 27 February 2012, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/02/27/jakarta-s-homework-and-maintaining-trust-aceh.html

-

Clarke et al., Considering victims, 16.

-

For more on the trials, see Yardley, ‘Politics in Bangladesh jolted by daily demonstrations’; ‘Bangladesh sentences third Jamaat-e-Islami leader to death’, Associated Press, 9 May 2013, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/may/09/bangladesh-sentence-third-jamaat-leader-death

-

Anis Ahmed, ‘Bangladesh amends war crimes law, mulls banning Islamists’, Reuters, 17 February 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/02/17/us-bangladesh-protest-idUSBRE91G05W20130217

-

For a more detailed discussion of the irregularities in the trial processes, see: Toby M. Cadman, ‘Bangladesh justice: Damned if you do, damned if you don’t’, Open Democracy, 5 March 2013, http://www.opendemocracy.net/opensecurity/toby-m-cadman/bangladesh-justice-damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-dont

-

Smruti S. Pattanaik, ‘Bangladesh war crime trial: The surprise second verdict’, IDSA Comment, 12 February 2013, http://idsa.in/idsacomments/BangladeshWarCrimeTribunal_SSPattanaik_120213.

-

Sayeeda Yasmin Saikia, ‘Beyond the archive of silence: Narratives of violence of the 1971 liberation war of Bangladesh’, History Workshop Journal 58, no. 1 (2004): 275–87, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/hwj/58.1.275

-

For a more detailed discussion of the Khmer Rouge era, see Phuong Pham et al., So we will never forget: A population-based survey on attitudes about social reconstruction and the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (Berkeley, CA: Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley, 2009), http://www.law.berkeley.edu/HRCweb/pdfs/So-We-Will-Never-Forget.pdf; Scott Luftglass, ‘Crossroads in Cambodia: The United Nations’ responsibility to withdraw involvement from the establishment of a Cambodian tribunal to prosecute the Khmer Rouge’, Virginia Law Review 90, no. 3 (2004): 893–964, http://www.virginialawreview.org/articles.php?article=25; J. Eli Margolis, ‘Trauma and the trials of reconciliation in Cambodia’, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 8, no. 2 (2007): 153–61, http://journal.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/8.2-Margolis.pdf

-

Luftglass, ‘Crossroads in Cambodia’.

-

For more detailed discussion on the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) trials, see Lina Gong and Manpavan Kaur, ‘Peacebuilding governance – Negotiating the Khmer Rouge trials’, NTS Alert, October, no. 1 (Singapore: RSIS Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies for NTS-Asia, 2011), http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/rsis/nts/html-newsletter/alert/nts-alert-oct-1101.html

-

Sok Khemara, ‘Khmer Rouge victims to take stand at tribunal this week’, Voice of America, 28 May 2013, http://www.voacambodia.com/content/khmer-rouge-victims-to-take-stand-at-tribunal-this-week/1669408.html; ‘Khmer Rouge victims’ testimonies continue at tribunal’, Voice of America, 6 June 2013, http://www.voacambodia.com/content/khmer-rouge-victims-testimonies-continue-at-tribunal/1675878.html

-

Thorsten Bonacker, Wolfgang Form and Dominik Pfeiffer, ‘Transitional justice and victim participation in Cambodia: A world polity perspective’, Global Society 25, no. 1 (2011): 113–34, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2010.522980

-

Personal interviews with representatives of several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Phnom Penh, August 2011.

-

Yoseph Yapi Taum, ‘Collective Cambodian memories of the Pol Pot Khmer Rouge regime’ (ASIA Fellow conference paper presented at the Fifth Annual Conference, Bangkok, 25–26 July 2005), http://www.asianscholarship.org/asf/ejourn/articles/yoseph_yt.pdf

-

Open Society Justice Initiative, Political interference at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (New York, NY: Open Society Institute, 2010), http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/reports/political-interference-extraordinary-chambers-courts-cambodia

-

Open Society Justice Initiative, Recent developments at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia: June 2011 update (New York, NY: Open Society Foundations, 2011), http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/reports/recent-developments-extraordinary-chambers-courts-cambodia-june-2011

-

Wendy Lambourne, ‘Transitional justice and peacebuilding after mass violence’, The International Journal of Transitional Justice 3, no. 1 (2009): 28–48, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijn037

-

For a more detailed discussion of the human rights violations, see Geoffrey Robinson, ‘East Timor ten years on: Legacies of violence’, The Journal of Asian Studies 70, no. 4 (2011): 1007–21, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0021911811001586; Jeff Kingston, ‘East Timor’s search for justice, reconciliation and dignity’, in Atrocities and international accountability: Beyond transitional justice, ed. Edel Hughes, William A. Schabas and Ramesh Thakur (Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 2007), 81–97.

-

Taina Jarvinen, ‘Human rights and post-conflict transitional justice in East Timor’ (UPI Working Papers no. 47, Helsinki: Ulkopoliittinen instituutti – The Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA), 2004), http://www.isn.ethz.ch/isn/Digital-Library/Publications/Detail/?ots591=0c54e3b3-1e9c-be1e-2c24-a6a8c7060233&lng=en&id=19246

-

Ibid.

-

Lia Kent, ‘Local memory practices in East Timor: Disrupting transitional justice narratives’, The International Journal of Transitional Justice 5, no. 3 (2011): 434–55, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijr016

-

‘Video interview: José Ramos-Horta, former President of Timor-Leste’, United Nations University, 5 December 2012, http://unu.edu/publications/articles/video-interview-jose-ramos-horta.html; Jeffrey Kingston, ‘Balancing justice and reconciliation in East Timor’, Critical Asian Studies 38, no. 3 (2006): 271–302, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14672710600871430

-

Kingston, ‘East Timor’s search for justice’.

-

Dionisio Babo-Soares, ‘Nahe biti: The philosophy and process of grassroots reconciliation (and justice) in East Timor’, The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 5, no. 1 (2004): 15–33, http://courses.washington.edu/war101/readings/Babo-soares-reconciliation.pdf

-

For more information on the Timor-Leste Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR) and its report, see the CAVR website at: http://www.cavr-timorleste.org/

-

Robins, ‘Challenging the therapeutic ethic’.

-

World Bank, Defining heroes: Key lessons from the creation of veterans policy in Timor-Leste (World Bank, 2008), http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2008/09/10526689/defining-heroes-key-lessons-creation-veterans-policy-timor-leste

-

International Center for Transitional Justice, ‘Unfulfilled expectations: Victims’ perceptions of justice and reparations in Timor-Leste’ (Brussels: International Center for Transitional Justice, 2010), http://ictj.org/publication/unfulfilled-expectations-victims-perceptions-justice-and-reparations-timor-leste

-

Kent, ‘Local memory practices in East Timor’.

-

World Bank, ‘Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above)’, accessed 10 June 2013, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS

-

Saikia, ‘Beyond the archive of silence’; Kent, ‘Local memory practices in East Timor’; and Lambourne, ‘Transitional justice and peacebuilding after mass violence’.

-

Phuong Pham et al., After the first trial: A population-based survey on knowledge and perception of justice and the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (Berkeley, CA: Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley, 2011), http://www.law.berkeley.edu/HRCweb/pdfs/After-the-First-Trial.pdf

-

Lambourne, ‘Transitional justice and peacebuilding after mass violence’.

-

Bonacker et al., ‘Transitional justice and victim participation in Cambodia’.

-

UN Development Programme (UNDP) Indonesia, ‘Project facts: Strengthening access to justice for peace and development in Aceh’ (Jakarta: UNDP Indonesia, 2008), http://www.undp.or.id/factsheets/2008/ACEH%20Strengthening%20Access%20to%20Justice%20for%20Peace%20and%20Development.pdf

-

Teresa Cierco, ‘Evaluating UNMIT’s contribution to establishing the rule of law in Timor-Leste’, Asia-Pacific Review 20, no. 1 (2013): 79–99, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13439006.2013.788335

-

‘UN to help Bangladesh war crimes trial planning’, Agence France Presse, 8 April 2009, http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5i8DOGtdoHAJaJQhtR_orq4CmvwOw

-

David Bergman, ‘Pakistan lobbied against UN help for war crimes trials’, New Age, 19 September 2011, http://newagebd.com/newspaper1/archive_details.php?date=2011-09-19&nid=33933

^ To the top |